FISH CAMP REMOTE

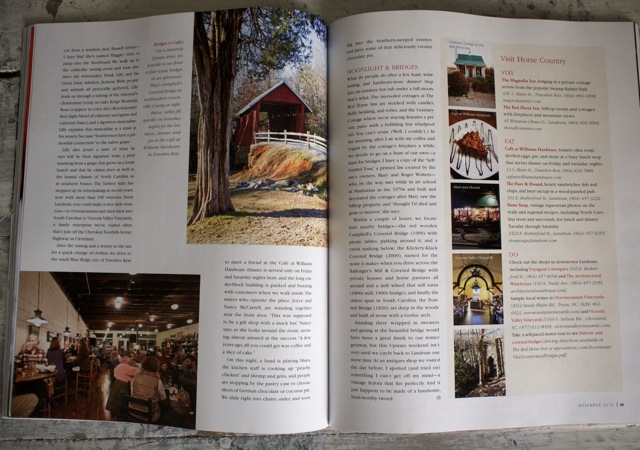

When you have to get to a place by floatplane, you’re either going somewhere, or nowhere. We collect their annual mailings. The last two are still stuck to the fridge by a single, tiny magnet—cards printed with lakeside musings and season’s greetings from Karen and Igor Sikorsky of the Bradford Camps “in the heart of the North Maine Woods.” One year, we tried to book a stay, but couldn’t find dates to mesh with our work schedule. Ever since, a new card arrives yearly to tease us with pictures of rustic log cabins, trout, and forests best reached by floatplane. Finally, we carve out another block of time and lock in on a plan for a stay over four late summer days.

To get there, we drive a few miles north of Millinocket to meet Jim Strang, a pilot at Katahdin Air Service, which shuttles mail, supplies, and people to and from many of the historic sporting camps. Hopping on his plane will save us from more than a half-day’s drive and the possibility of a few blown tires on unpaved logging roads. Once airborne, it’s easy to see that we’ve traded a rough and rutted route for easy and expansive views. Through the headphones, we hear Jim talk of the millions of acres of undeveloped land below us. As far as we can see is Maine’s great northern treasure.

Within 25 minutes, the plane flies over a four-mile-long a lake called Munsungan. Suddenly, there it is—on a stretch of the forested shoreline, the cabins and grounds of the Bradford Camps come into view. From a few dozen yards above the treetops, I see a large dog bound out into the water (that would be Moxie, a chocolate-colored retriever with a head like a brown bear), and then a man and a woman walk out from the porch of the lodge, and I surmise they must be Karen and Igor. The plane circles back and touches down on the water, and the engine putters like a motorboat as Jim guides it to park at the dock. We don’t have to imagine any more. We’ve arrived.

No laptops or mobile phones to fool with here—our two-room, lakeside log cabin for the next several nights is equipped with running water (cold and hot) and propane wall lamps, but no electricity. Igor and Karen give us a tour and encourage us to follow a trail into the woods for a walk before dinner. Not long after the floatplane disappears in the distance, I realize the gift of time and space we’ve just gotten. We follow the narrow path past a stream that gushes over stones to form what looks like a natural waterslide. A tremendous amount of mushrooms have sprouted, and we come back to the cabin with handfuls of chanterelles and few big lobster mushrooms that look just like claws. Without high-tech diversions, I find a pencil and start jotting observations in my paper notebook.

When the dinner bell rings we walk over to the lodge, along with the only other guests, a dozen men from New Jersey who’ve come as a group. They mostly keep to themselves and sit together at one long table in the dining room. Ours is a table by the window overlooking the lake, and I soon notice the mounted deer head in the dining room has a nonchalant look—there’s something carefree about the buck’s sleepy eyes. I look up at him between courses prepared by Matthew Mills, the camp chef who hails from New Hampshire and says he’s been here all summer, and cooks at a game preserve in South Carolina in wintertime. We’d wandered through the garden rows just yards from the kitchen door earlier, and saw beans, corn, greens, tomatoes, herbs, and more. Matthew makes good use of the harvest. Along with fresh bread, he cooks up dishes of haddock with a butter sauce, zucchini and squash, roasted prime rib, corn chowder, cubed watermelon with fresh mint, and more.

Naturally, we fall into the rhythm of this place. I go to the small wooden ice house behind the lodge and use one of the ice picks—Igor shows us how—to stab a gin-clear block until I’ve got enough shards and chunks to fill a small bucket to tote back to our cabin. Igor says he comes up to the camp by snowmobile every January with a group of friends to cut ice from the lake, and together they bury it under sawdust in the icehouse. Over the course of a summer, they’ve never run out, he says. I love this ice—the idea of it, and the taste. The first night after dinner, a group of us sit on the porch of the lodge after the generator has been turned off for the day. The only light is from the moon. We’re all talking, and at some point, Moxie laps up the melted ice and splash of whiskey in someone’s glass. Everyone’s laughing and then Karen and Igor recount the time Moxie picked up a lit cigar, and appeared to try to smoke it. My glasses of ice and water (and a cocktail or two), never tasted so sweet. A few of us wonder aloud if there’s a way to market these crystal clear cubes of lake.

We take turns looking at the silvery-white full moon through a telescope, and Igor starts a bonfire at the very edge of Munsungan in a firepit protected from the lake’s winds and water by a huge stone and the upright blade of a steel backhoe. (In a feat of man and equipment a few years ago, Igor says he moved the whole thing into place.) The pyre reflects in the water and sparks crackle and rise into the coal-black sky. I look back at the circle of men around the flame from a distance as we walk back to the cabin, and the scene looks historic, even pre-historic. Later I read in the propane lamplight until we fall asleep under quilts. Well past midnight I sit upright in bed, suddenly wide-awake and listening. At first I can’t process what I’m hearing, and I think the ruckus is the men’s group whooping it up at their card games in the cabins near ours. But soon I realize that it’s actually coyotes yelping—sounds like a roundup of pups very excited about something. A hunt? Someone had said that coyotes are supposed to be on the opposite shore of Munsungan Lake, but they sound much closer. I’m excited to be in a place so wild. But in the morning, some of the other guests say they heard nothing. “Good sleeping weather,” one man says, stretching his arms over his head. “I slept ten hours last night.”

The second afternoon, two loons are on the flat, calm lake in the hour before dinner. Sunlight is falling fast, and I see Karen is on the dock near where Igor’s plane is tethered and floating, as if it were a boat at a marina. I pull on my bathing suit, grab a towel and hurry down to the water. Karen says, “Let’s jump from the plane.” She shows me how to step around the propeller and get a foothold on one of the floats. She’s standing on one and I’m on the other, and like kids in a schoolyard, we decide to jump together at the count of three into the chilled water. Thunder is rumbling in the distance and I look at the ancient mountains across the water once more, before we both jump as high and far as we can. The lake feels so cold it must be on its way to becoming ice again, I think, and I gasp when I come up for air. After some splashing around, I dash back up to the cabin. I’ve got just enough time to change into a turtleneck and jeans before the dinner bell.

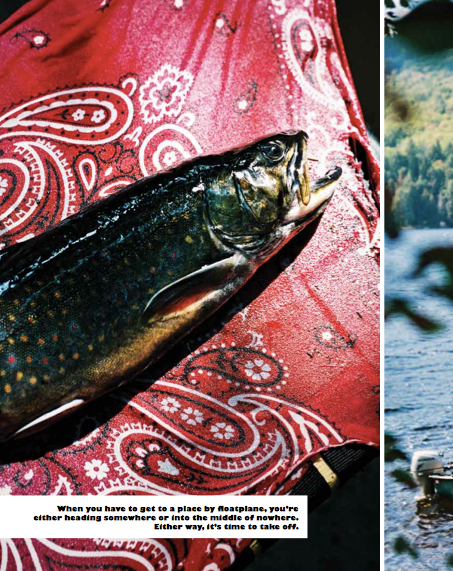

We hatch a plan to catch a native brook trout while there, and Igor and Karen know just the place, a nearby pond with an undeveloped shore. Even better, they suggest that we all go in Igor’s floatplane the next day to get there—taking along fishing poles, gear, and a cooler of sandwiches and drinks from the lodge kitchen. It’s our third day at the Bradford Camps, and in a few minutes we land on the pond—the name and location of this fishing honey hole is a secret—and Igor cuts the engine and uses a paddle to guide the plane over to a spot on the bank where he keeps canoes. The pond is restricted to fly fishing only, and we each take turns casting. All’s quiet for an hour, and then Karen is the one to get a hit, and she reels in a brookie of keeping size—its gold and red spots gleaming on an olive brown body. We land one more, but wrap only one fish in a red bandana to bring back to Matthew at the camp’s kitchen. The trout is a beautiful treasure, and we carry it carefully.

The next day is when we’re scheduled to leave the camp. We pack and then meet Matthew, where he’s already frying the whole trout for us in a skillet. I don’t think guests typically go into the kitchen, but we’re comfortable amid the shelves of plates and cups, the loaves of rising bread, and the big pot of squash soup that’s already simmering on the stove for the day’s lunch. We’ve waited so long to get here, and we’re still taking in as much of the Bradford Camps as we can. When the fish is plated and ready, we don’t go to the dining room. Instead, we all find forks—Karen and Igor, too—and taste the wild-caught trout that’s pink-fleshed and incredibly delicate and delicious. We talk of the prior day’s fishing and of other happenings in the several days since we’ve arrived, stopping when Karen turns up the volume of a radio for the daily “Writer’s Almanac” segment on NPR—listening to this is apparently a ritual at the camp. Everyone in the kitchen goes quiet and still for these moments as announcer Garrison Keillor reads a poem by Hayden Caruth. It’s a thoughtful verse, something to mull over and discuss, but through the screen door, we already hear the distant buzz of Jim Strang’s plane. Too soon, he’s coming to return us to the everyday world—where time for such things as poetry, fishing, and jumping from float planes is simply too damn rare.

– Sandy Lang for Maine magazine, June 2012 issue