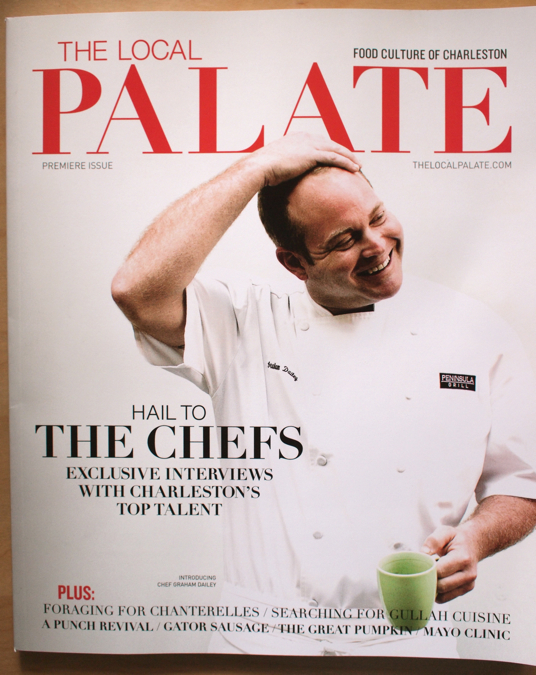

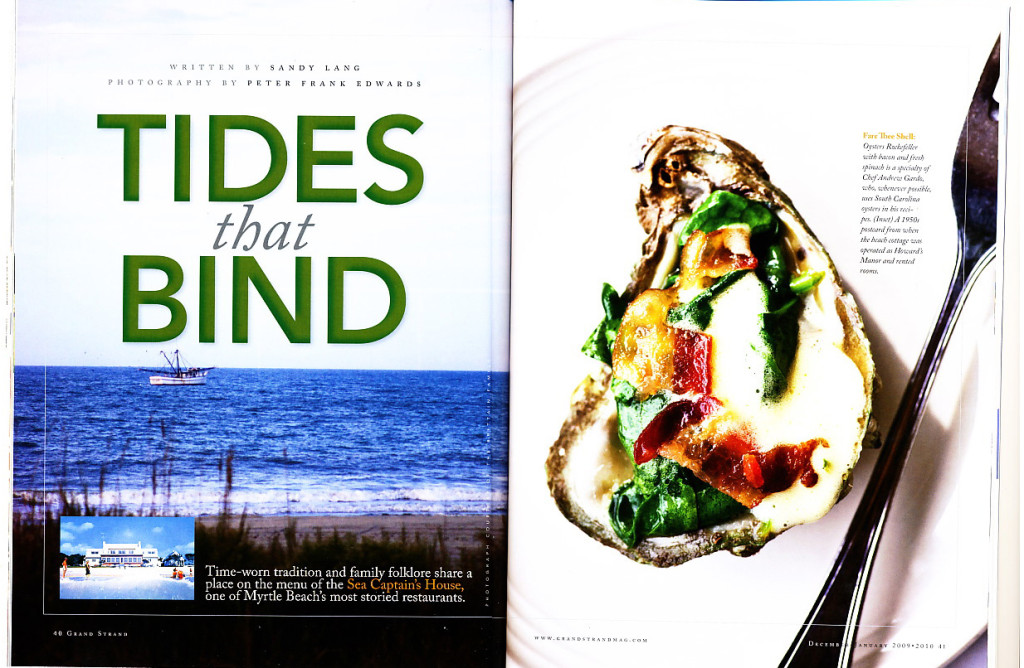

For a winter issue of Grand Strand magazine, I had the chance to write a cover story about a restaurant I’ve known since I was a teenager – the old Sea Captain’s House, oceanfront in Myrtle Beach. The story and images filled nine pages in the magazine. Here’s a shorter version..

At one of the granddaddy restaurants of Myrtle Beach, the grandfather of 10 had just finished a shrimp po’ boy lunch when he leaned back in his chair and talked of his first years with the restaurant, nearly 50 years ago. Just over the dunes from the pine-paneled dining room at the Sea Captain’s House, the ocean was slate-gray and rising with waves from a sudden winter storm. But where Clay Brittain sat with his family, in the comforts of the restaurant’s “Chart Room,” all was snug and warm, with the smells of sweet fried hushpuppies still rising from woven baskets on the table. It’s the same room where Mr. Brittain, now officially retired, will celebrate his 80th birthday later this month. He and his uncle Steve Chapman founded the Sea Captain’s House in 1962.

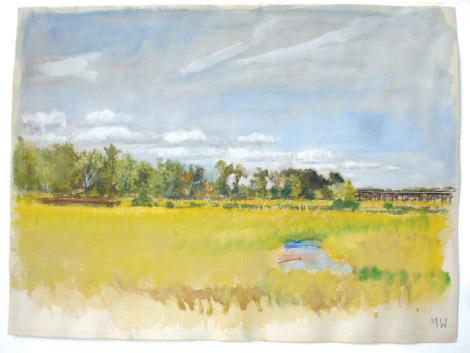

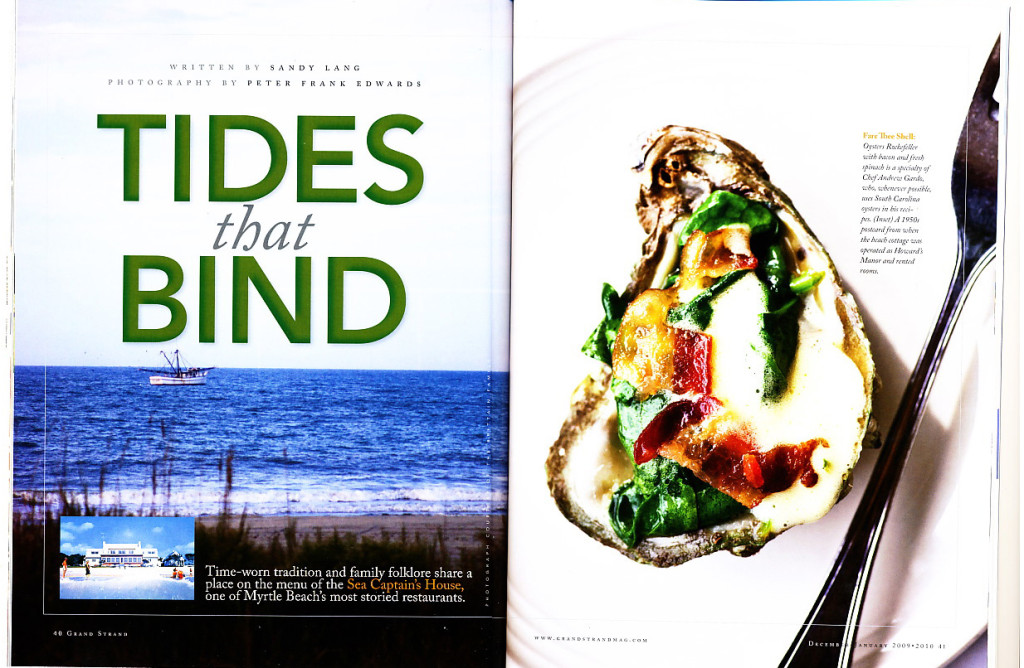

‘Tis the season of cozier festivities for the Grand Strand, and notably for a classic gathering place like the Sea Captain’s House, at 30th Avenue North and Ocean Boulevard. Housed in a 1930s beachhouse and former guesthouse, the restaurant’s traditions of food and family fill the space year-round – a modest shingled cape set beside a towering line-up of the strand’s oceanfront hotels.

The core rooms of the original home have remained little-changed through the decades, set with upholstered furniture and game tables for checkers and dominoes. (I first ate at the Sea Captain’s House as a student in the 1980s, and felt the history immediately.) Even more so today, stepping inside the restaurant is like re-entering another era in Myrtle Beach – back when the Pavilion still drew crowds along a wooden boardwalk, and had bathers’ changing rooms, photo booths, and Skee-Ball machines.

History and family traditions are alive and well at the Sea Captain’s House, where the Brittain and Chapman names are still synonymous with the restaurant. It’s now operated by the next generation of Brittains – brothers David and Matthew Brittain and their wives, Ann and Marie-Claire. Steve Chapman, grandson of the co-founder, grew up at the restaurant, and his father, Bob Chapman, managed the restaurant for many years. Seven of the ten Brittain grandchildren – all in their teens and early 20s – worked in the dining room last summer.

The landmark restaurant still serves three meals each day – from grits and fried egg breakfasts, to lunches and dinners of house specialties like fresh-made crab cakes, chowders of chopped clams, and South Carolina oyster singles on ice served with a champagne mignonette. In a recent conversation with Phil Ratcliff, one of the chefs, he easily put his hands on an original menu for the restaurant, and pointed out many dishes that are still served. “The prices are pretty nice from when Mr. Brittain set this up,” he said, and started reading some of the list… $2.25 for the Seafood Platter, Shrimp Creole for $1.75, and desserts for 25 cents each.

Mr. Brittain and his wife, Pat, recall those early days well, and the recipes they collected when the restaurant began serving food back in early 1960s. There’s the She Crab Soup with cream and sherry from a Charleston recipe; the Avocado Seafarer, made with lump crabmeat and avocado; and the Sea Island Shrimp, from a recipe shared with the Brittains by a home economics expert who was a frequent guest at the Chesterfield Inn, two miles south. “Now, that’s a great recipe,” Mr. Brittain said of the popular cold shrimp dish that’s marinated with capers and onions. “It comes from when the Sea Islands had no electricity, so they’d pickle the shrimp, even burying it underground to keep it cool.”

Today, the restaurant regularly serves hundreds of customers each day, with two longtime chefs – Ratcliff and Andrew Gardo – leading the busy kitchen and creating daily specials with each day’s delivery of fresh seafood. New seating areas have been added over time, but other changes have been few. The biggest the family can point to are how in the 1980s, beer and wine was added to the menu, and two years ago, live music on the patio was added for the first time. And whenever they make any changes, the family says, rumors often follow that the restaurant might be torn down, as has happened with so many other buildings of old Myrtle Beach.

At the weekly lunch meeting with his family, when Mr. Brittain talked of the history of the well-worn restaurant, the mention of such rumors brought a teasing twinkle to his eye. Running the restaurant was never intended to be long-term proposition. “It’s still temporary!” he declared. His wife, sons and daughters-in-law smiled. Then, as sure as a shrimp boat chugged past the ocean-facing windows and the hum of conversations filtered in from other dining rooms, they all talked of plans for another holiday season and the new year.

– February 2010, Sandy Lang (images by Peter Frank Edwards)