A summer visit to John Duckworth’s studio…

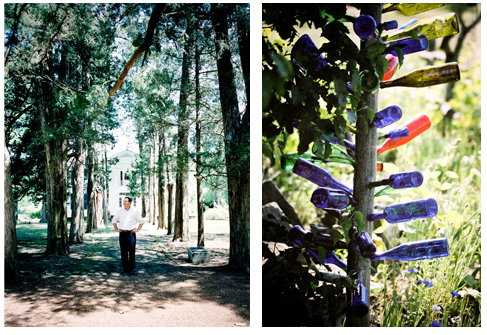

There’d been a ruckus in the yard that morning, John Duckworth said when I drove up. A neighbor’s dog had carried off one of his flock of young chickens and feathers flew, but the hen survived. A black-plumed rooster was still nervously scurrying between the 100-year-old farmhouse and the barn-sized building that’s now an art studio. Duckworth wasn’t unsettled though, and stood patiently watching the yard. He offered to brew some tea.

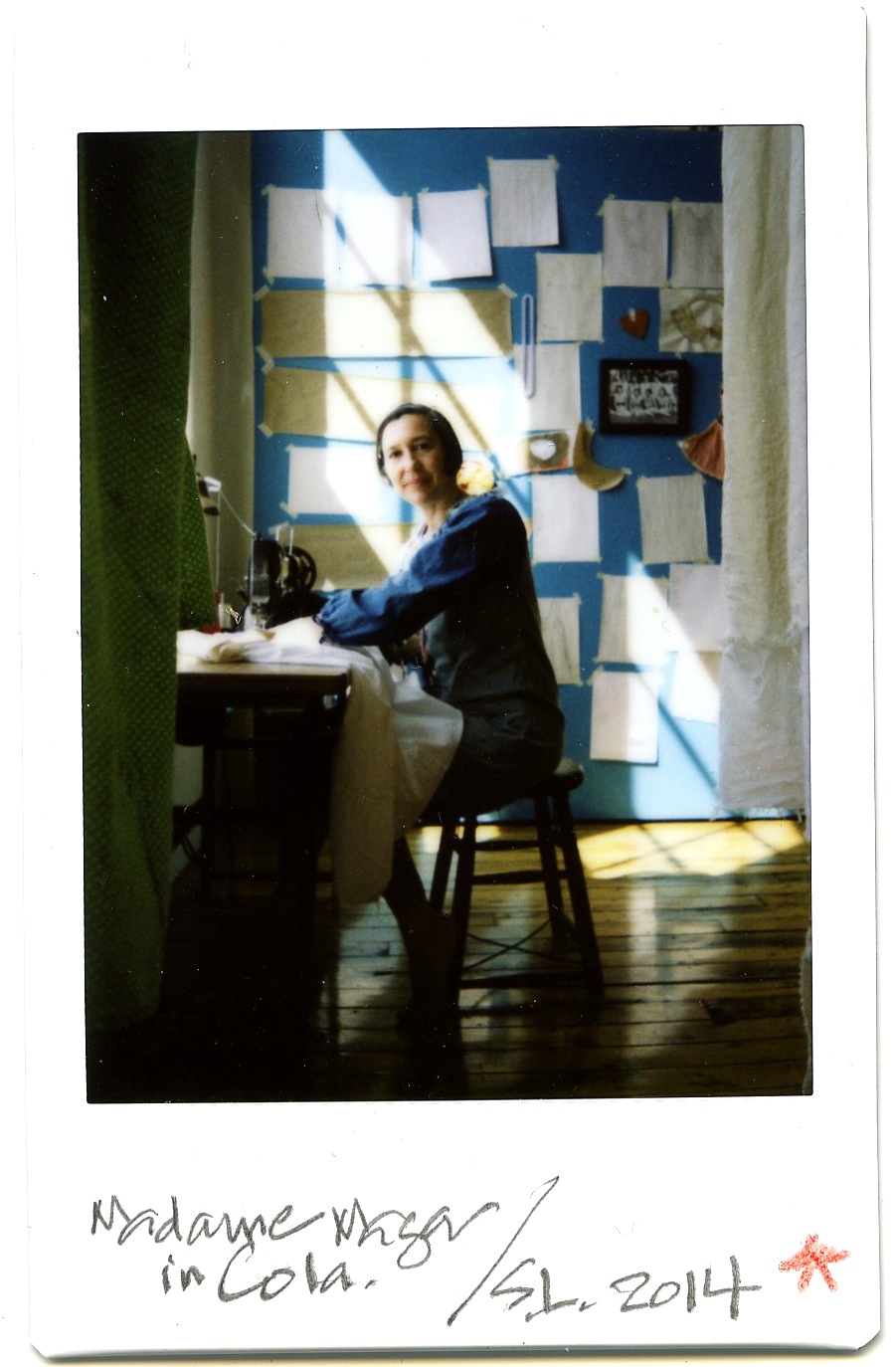

Where a writer writes, where a painter paints – these are important places. Duckworth’s is a lofty studio, with oversized canvases set on easels and hung from wheeled tracks that allow paintings to be slid into and out of view. On another wall, there are computers with the broad screens needed for the digital aspects of his photography. (When we walked in, his assistant was mapping the effect of slight color variations on a specific print.) The studio building itself is a rustic compilation of found materials – walls of reclaimed beadboard and wide pine, of rough stucco-covered brick, and a mix of striated and smooth cement blocks. The artist hasn’t renovated to hide or replace any of these mismatched elements, all of which he says existed when he bought the place a few years earlier. Rather, he tells visitors what he’s learned about the origin of the materials – specifics about bricks from a South of Broad tear-down, or planks from an island barn.

A few dozen yards away, Duckworth’s white-painted, tin-roofed house of porches, wood floors and single-paned windows is pure early-20th century rural South. There’s no television inside. Instead, there’s framed art on the walls (his and others), a well-used fireplace, and a spare amount of wood furniture. On tables, sills and countertops, there are found bones, feathers, and shed cicada bodies – a goldfish in a bowl, two tiny frogs in a terrarium cube. That morning there were also glass jars of moths and butterflies at various stages of development – a collection of cocoons and caterpillars that he’d been observing with his 5-year-old son, Baze, and then labeling the jars with notes about each insect’s diet and what to expect when it transforms and takes wing.

The artist and single father is California-born, but has obviously found a comfortable place on this sea island so near to downtown Charleston, South Carolina. He used to rent an apartment in the 300-year-old city and often still makes the peninsula a subject or backdrop of his art. Duckworth paints and photographs the landscape, people, animals and elements around him. Wood fires in his firepit last winter led to photographs of wispy smoke that look like sheer fabric blowing. Horse farm visits with Baze inspired the artist to create a series of horse portraits painted over landscape photographs. And Duckworth still shoots and prints photographs of the marsh expanses, a passion born of bicycling on Johns and Wadmalaw islands and being struck by the beauty, color and peace of the wide landscape. He explains that he’s continually experimenting and blending these passions for photography and painting – studying the masters, mixing old techniques with new.

After final looks at some of this island artist’s current projects, I’m back in the car and ready to drive off from this visit, when a sudden mid-day rainfall erupts. Big drops sheer the windshield, and I think of the built and natural scenes that are so often Duckworth’s subjects – paintings and images almost always out of clear focus. Viewing his art, I think, as I pull away from the island farm, can be like looking through rain on glass.

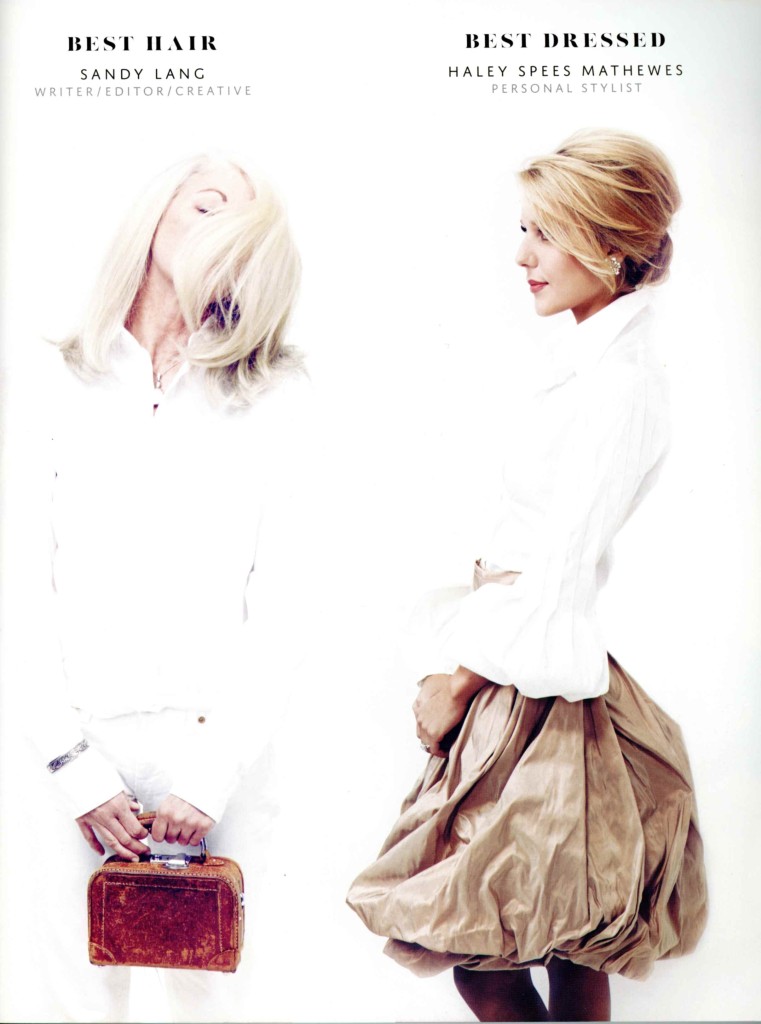

– Sandy Lang, June 2010 (Images by Peter Frank Edwards.)

I’ve got a new travel feature in this month’s

I’ve got a new travel feature in this month’s