When I stopped in to see photographer Jack Thompson one day this winter, he suggested we go for the buffet at Shoney’s in Myrtle Beach. While we ate, he told stories and I wrote up the interview for Grand Strand Magazine. The piece runs for 10 pages in the February-March 2010 issue, filled with Mr. Thompson’s images. Here’s an excerpt…

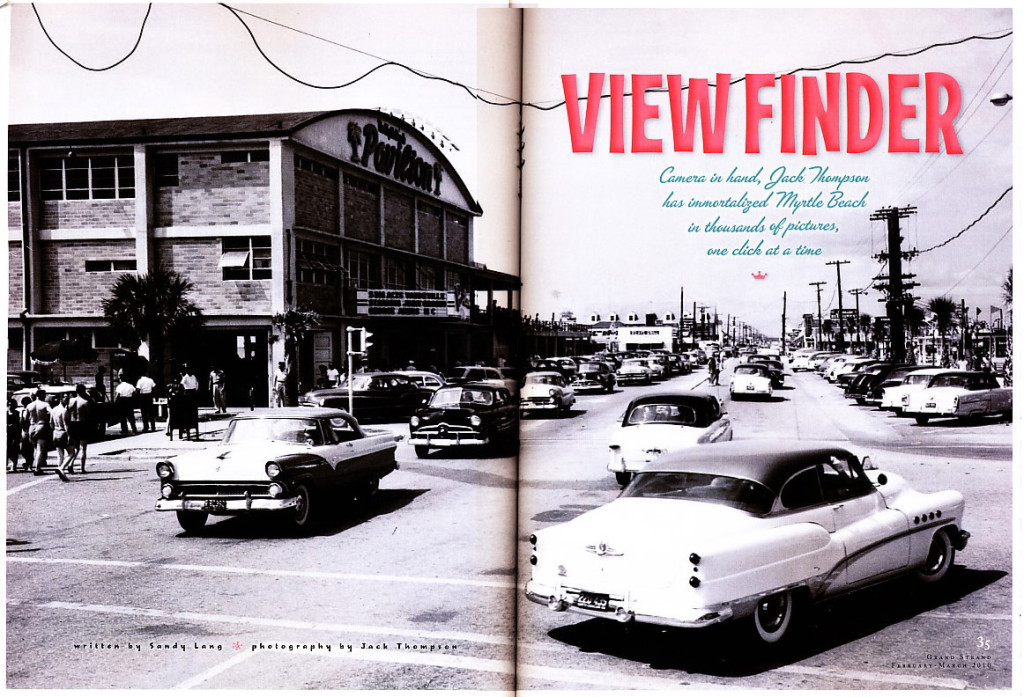

A 1950s motel on the Boulevard, the night sky lit with fireworks over a dirt lot at the Pavilion’s amusement park, a sunny beach day in the 1960s.

Jack Thompson, 73, sorts through stacks of his black and white photographs – some framed, some loose or mounted on boards – in his storefront studio on Broadway Street. It’s his fifth location in as many decades, always in buildings within a sea breeze distance of the Myrtle Beach Pavilion. (Or nowadays, the empty grass lot and beach where the Pavilion once stood.)

In these blocks that are the historic heart of Myrtle Beach, Thompson and his photographs help remind people of the city’s beginnings, and particularly of the classic mid-century era. That was when, with two other teenaged boys from his hometown of Greenville, Thompson rode on the back of farmers’ truck beds and in un-airconditioned buses to get to Myrtle Beach. (The boyhood friends who joined him were Freddie Collins, who’d later become a millionaire in the business of poker machines and other amusements; and Carroll Campbell, who’d one day be Governor of South Carolina.) The boys had heard stories from older friends back in Greenville of the sandy lifestyle – of the beach music, beer and beautiful girls to be found. After several days of often-misdirected travel on two-lane highways (including mistakenly catching a ride to Orangeburg, and then up to Society Hill where they slept one night under a church), Thompson says the three finally arrived in downtown Myrtle Beach, exhausted, hungry and broke.

He remembers that day well. Thompson says he could see the Pavilion from the bus stop, and walked directly to it. The year was 1951…

His legacy is a still-growing collection of beautiful prints. And it’s the black and whites that really grab you. They are striking and classic, even iconic, and look of a simpler past you could step into. When he talks of his work, Thompson is a mix of humble and proud. And he’s quick to say that the subjects are often “ordinary” scenes – ordinary for the happenings and scenery of the times.

“Now people say, ‘Jack, you must have been a damn genius.’ But if I was, I didn’t know it at the time. These pictures are of what was everyday… it was just the way it was.”

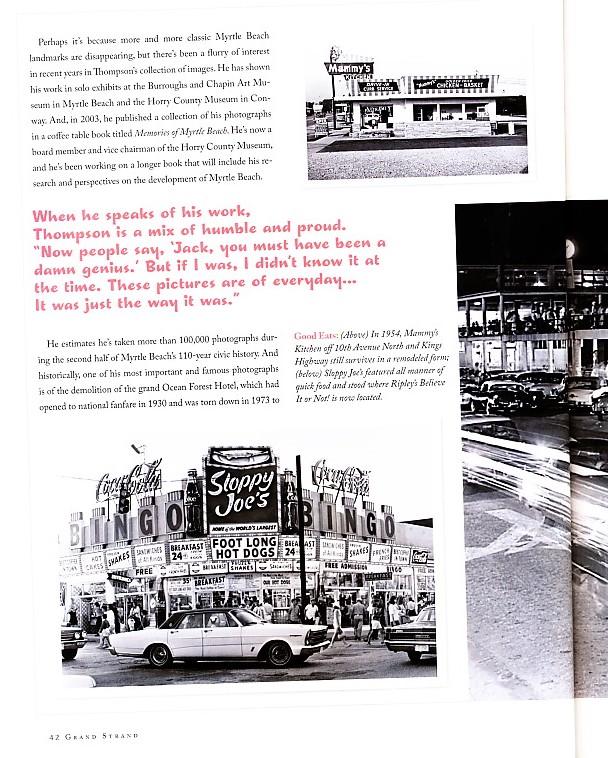

Perhaps it’s because more and more classic Myrtle Beach landmarks are disappearing, but there’s been a flurry of interest in recent years in Thompson’s collection of images. He has shown his work in solo exhibits at the Burroughs and Chapin Art Museum in Myrlte Beach and the Horry County Museum in Conway. And in 2003, he published a collection of his photographs in a coffee table book titled “Memories of Myrtle Beach.” That book also includes a summary of the history of Myrtle Beach, a subject of keen interest to Thompson. In fact, he’s a board member and vice chairman of the Horry County Museum, and he’s been working on a longer book that will include his research and perspectives on the development of Myrtle Beach.

Historically, one of his most important and famous photographs is of the demolition of the grand Ocean Forest Hotel, which had opened to national fanfare in 1930 and was torn down in 1973 to make way for an oceanfront condominium development. “When I was there that day, and I found myself setting up my camera on a strategic sand dune, I knew in my heart that the governor, the mayor, or the fire chief or somebody was going to come in and stop the demolition, because of what this hotel meant to this part of this state,” Thompson recalls. “Then I heard the first explosion, and I started crying… I had grown up in that hotel, photographing famous personalities and conventions night after night. I could not believe that men of vision did not step in and save it.”

These days, Thompson remains one of Myrtle Beach’s fondest admirers. And he knows the city has reputation for continually reinventing itself, yet he’s cautiously optimistic about the future. “Policy makers will have to keep a strong vision,” he advises. Thompson says he was disappointed at the recent closing and demolition of the centrally-located Myrtle Square Mall, and especially of the loss of the 11-acre Myrtle Beach Pavilion & Amusement Park “The powers that be destroyed a magical place… it’s a heartbreak and a tragedy.” The big question is, he says, “how do you put the genie back in the bottle?”

– Sandy Lang, March 2010