MY BIG FAT GREEK EASTER

Into the kitchen and a happy cacophony (from the Greek kakophõnia). That’s how this dinner begins. Words over words—some in English, some in Greek—come from all corners of a second-floor kitchen that’s eye-level with the sprawling branches of live oaks. Sisters, aunts, sons and friends are gathered at the Mount Pleasant home of Georgia and John Darby, in one of the family houses on the original Seaside Farms acreage on Rifle Range Road.

The day’s lively talk is of food and family and Easter. Final prep for a traditional Greek Easter meal is in full swing. On the kitchen’s center island are platters and roasting pans, knives and cutting boards—lemons, tomatoes, pomegranates, olives, bricks of feta and bottles of olive oil. Helen Theos, a longtime family friend (an unofficial “Aunt”), is arranging a platter of bread and hens’ eggs that have been dyed ruby red. Akaterine “Katie” Bohren checks the progress. “It’s got to look like grass,” she says, of the prasa fronds they’re using to create a green bed under the eggs. She suggests cutting shorter strands. Katie was born in Greece and became friends with the others through the Greek Orthodox Church in Charleston, a hub of Greek culture here. Katie and her sons used to have a Mediterranean restaurant named Niko’s, and for this dinner, she’s prepared and brought the garlic and oregano-rubbed leg of lamb that will be the centerpiece of the meal. Her potatoes baked in lamb drippings and lemon juice are warming in the oven.

When the “grass” is cut to everyone’s satisfaction for the platter of red eggs, Katie and Georgia begin assembling a chopped “village salad“ of tomato wedges, onions, peppers and goat cheese. “A true Greek salad has no lettuce,” Georgia notes. Demetre Homer, her brother, has joined the group in the kitchen and is talking of the merits of the cheese-filled Greek pastry Tiropeta over the more popular spinach and filo-layered Spanakopeta. “I could eat Tiropeta every morning,” he says. Charleston-born and fluent in Greek language, Demetre says he’s spent nearly half of his life in Athens, and now lives in the upstairs apartment of a King Street storefront building that his great-grandfather purchased when he emigrated from Greece to Charleston in the early 1900s.

Christine Homer, mother of Georgia, Demetre, and Alexis, is hungry. She moves about the kitchen watching the food prep, and looking for something to sample before dinner. “Other people get together to exercise, we get together to eat,” she says. The family asks Christine and Helen to share some memories and Easter traditions. The two have been friends since the late 1950s, when Helen, from Charlotte, moved to Charleston as a new bride and joined the Greek Orthodox Church on Race Street. The women estimate that they and their families have celebrated more than 40 Easter dinners together.

Christine remembers that her mother would follow a “true” 40-day fast before Easter by eating no meat, milk or eggs. The Lenten fast is broken each year with a midnight meal of Margeritsa, a soup of organ meats from a lamb, she says. This is a holdover from when an entire lamb would be consumed—the roasted leg meat is eaten the following day, on Easter Sunday. (Note: the date of the annual Greek Orthodox Easter observance must follow Passover, and does not always match the Easter observance in other Christian churches. This year, Greek Orthodox Easter is observed on April 15.)

Helen says she moved to Charleston just as the first edition of the Popular Greek Recipes cookbook was being compiled by the Charleston church’s women’s group, the Ladies Philoptochos Society. By the second edition in 1965, she was part of the revision committee, and the four additional revisions since then. “I’ve cooked every recipe in the book,” Helen says. On Easter, the tradition is for the men to roast the lamb outside. “We’d serve Bloody Marys,” she says. “If you were young, you ate at tables outside… we used to be the young ones!”

Georgia’s husband, John, smiles at the buzz of people, food, and conversation in the kitchen. He’s the grandson of J.C. Long and the CEO of The Beach Company in Charleston. “My life is sometimes like the movie My Big Fat Greek Wedding,” he says. He does not have a Greek family history himself. He explains that he and Georgia met in the 1970s while students at Bishop England High School. She adds, “I’d never eaten an oyster, and he’d never eaten lamb.” The couple later married and have three children, and the youngest, Litsa, is a high school senior. She’s the one who, once at the table, encourages everyone to lift the red egg from the silver egg cup at each place setting, and tap it against someone else’s egg. This is a tradition, and if you’re egg doesn’t crack, she says, it’s good luck. Everyone picks up eggs, instantly getting beet-like stains on their fingertips. “This is the way your fingers look at Easter,” Christine says, showing her reddened fingers. She and her granddaughter, Litsa, are the final two with un-cracked eggs until they reach across the table for a vigorous tap. (Christine is a retired school coach, and Litsa is on the volleyball team at Ashley Hall School.) Christine’s egg isn’t even dented, and there’s a roar of laughter. “I mean, she really smacked it,” Helen says.

By now, afternoon light is flowing through the dining room’s tall windows and across the long table. Greek wine has been poured (and some Ouzo, too), and the handsome group is high spirited. As or the food, the table’s greatest praise is being given for the honey-glazed figs, the twists of buttery Koulourakia, and the roasted lamb, with its salty herb crust. On the walls around them is a mural the Darbys commissioned from artist Robert Shelton. In its earth tones and almost dream-faded landscapes, the painted scene looks at first to be of Mediterranean Greece, with olive and fig trees, pomegranates and grape vines. But then you notice what’s even more familiar: Palmetto trees, live oaks and herons. As the talk flows and the plates are passed, some of Greece and the South Carolina Lowcountry blur and blend into one.

– by Sandy Lang for The Local Palate, March 2012

OYSTER DRIVE

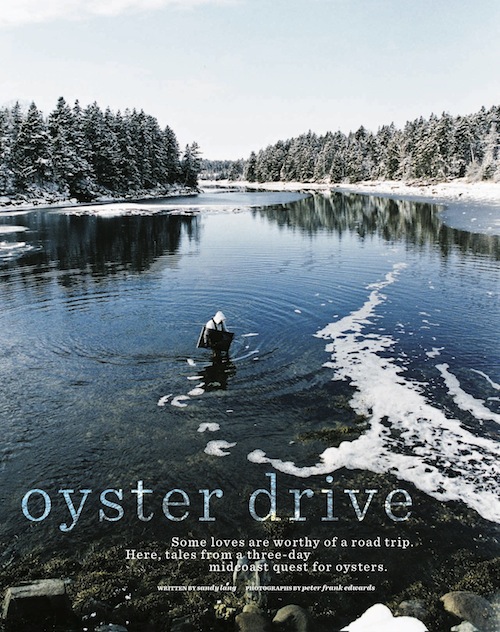

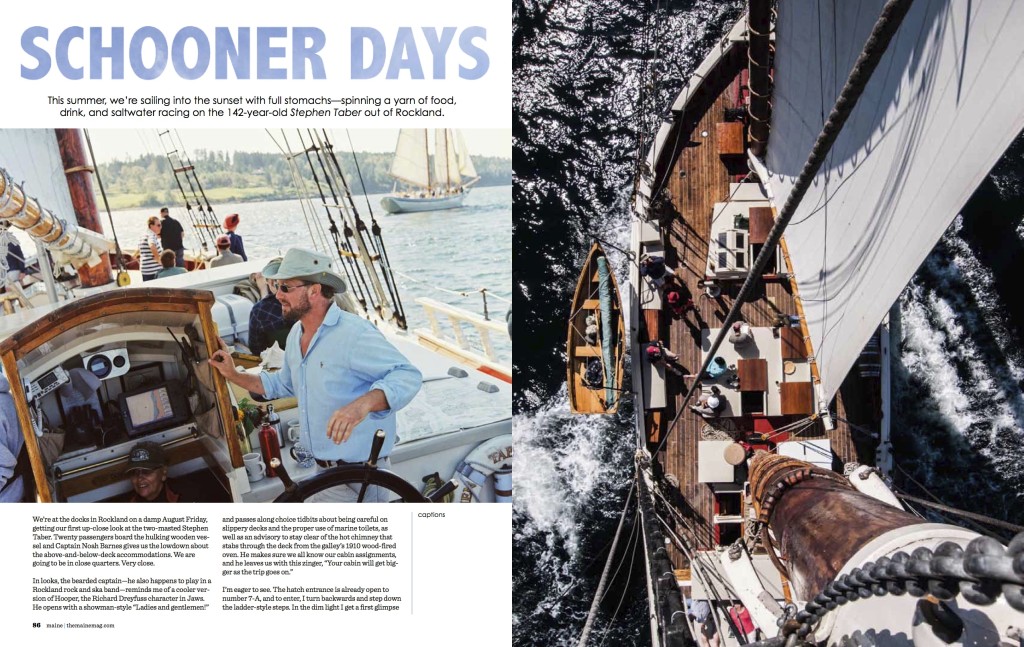

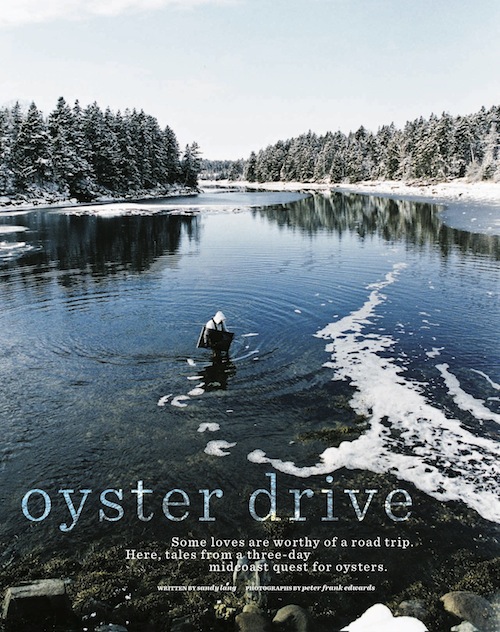

Take a flight into Portland, and power directly north on some combination of Route 1 and I-95 to the cabin near Bucksport. That’s what we typically do—but not this time. It was a mid-December morning, snow was coming, and it was just days before many of the oystermen would be hauling in their boats and gear for the season. (Some harvest year-round. Others are typically back out on the water in March or April.) That’s how our “Oyster Drive” was born.

Weather and season made it suddenly more than a fleeting idea. Finding oysters was elevated to a personal mission—something necessary, even urgent. As winter crept up from the floorboards of the rented Toyota, every oyster we could find would be that much more precious. We mapped out a plan to skip I-95 and stick to the coast, seeking roadside views of the tidal beds and washes where the oysters grow, and making stops along the way at towns, coves, rivers, islands. We wanted to taste again the salt and quiver of the Maine oyster, and get our fill as close as possible to the chilled tides. The gas tank was full, we had the Maine Atlas and Gazetteer by our side, and we had a starter list of oyster destinations in hand. Check. Check. Check. Off we went.

day one: edgecomb to spruce head

An hour or so north of Portland, if you hang a right off of Route 1 at Newcastle (love a town with a beer name), you’ll eventually find the Glidden Point Oyster Sea Farm. It’s on the southern end of River Road, past five rolling miles of woods, barns, and short side roads that end at the Damariscotta River below. The primary feature at Glidden Point is a tidy walk-in shed where oysters and clams are arrayed in bins in glass-door coolers, and payment is by cash or check (on the honor system). Sometimes wetsuits are drip-drying on the porch rail. Owner Barb Scully’s teenaged children help her harvest the oysters, which can involve diving ten to forty feet below the surface of the Damariscotta. On that day of bare-limbed trees and fast-falling snow, Barb was in the yard dressed in a black Grunden’s jacket, blue jeans, and suede boots. She has a degree in zoology and has been oystering on the Damariscotta for more than two decades. “It’s a very productive estuary,” she says.

I’ve tasted the oysters she harvests, thick shelled and heavy after growing in cold water. Maine oysters like Glidden Points are known for their complex flavor—sweet and briny—that Barb says comes from the oysters’ storing energy as glycogen to adapt to wintertime. I’m interested in this bit of science, since I’ve lived much of my life on the South Carolina coast where the oysters grow much faster in warm, silty creeks. Southern oysters are deliciously familiar to me, but an experience very different from the crisp and clean, firmer-textured oysters of Maine.

It was time for lunch. We drove back up the five miles toward Route 1, where the Damariscotta River cuts between the towns of Damariscotta and Newcastle. Oysters are literally part of the landscape here, with massive heaps of oyster shells—built up over the centuries by Native Americans—still lining the river’s banks. Jed Weiss mentioned the middens at some point in our conversation at cozy King Eider’s Pub, where we had slid into a narrow room upstairs to sit at the two-stool raw bar. Weiss is one of the pub’s owners and was opening Dodge Cove oysters one by one using a built-in shucking tool created by the restaurant’s founders. As he worked with the glistening oysters, the legendary Damariscotta could be seen out the window. “On a good day,” he said, “you can almost see the lease where these oysters come from, just a mile down the river.”

That first dozen went down easy. Back outside, flurries blew, passing cars braked and slipped, and the snow blanket was getting thicker on Main Street, which is lined with brick-façade stores and cafes. I thought of the nearby midden banks, now certainly covered in white. We ducked into the original Reny’s for some road-trip gear, and the sixty-one-year-old department store didn’t fail us. In Reny’s Underground we picked up American-made wool caps for $3.99 and cotton utility gloves for $1.14 a pair—perfect for oyster shucking. Next stop would be the Newcastle Publick House, where two watermen sat at the bar with not-so-faint diesel fumes lingering on their coats. While tourists love this slice of midcoast Maine, it’s also still a fishing town. I like that. We sat at a table by the fireplace and ordered a plate of “Angry Al’s” Oysters—baked jumbo Pemaquid singles topped with bacon, spinach, Gorgonzola cheese, and hot sauce.

Then, like it was destiny, oysterman and musician Jeff “Smokey” McKeen walked in, ruddy faced and in a red-plaid wool coat, his wild silver hair blown tall by the wind. Smokey plays button accordion and banjo with the Celtic folk band Old Grey Goose, and would be difficult to miss on his travels up and down the coast delivering the Pemaquid Oyster Company oysters he harvests from the Damariscotta River. He says they’re “the best, most plump, and sweetest.” And the taste of the Angry Al’s version? The house-made hot sauce gave it a good kick, and the blue cheese added twang. But beneath the preparation, Smokey’s oysters held their own.

We talked some more of music and oysters and then needed to keep moving. I called ahead to Barrett Lynde of Gay Island Oysters, and we agreed to meet at a dock past Maple Juice Cove, near the end of the Cushing peninsula. “The bridge at Salt Pond is closed,” he’d told me, “so you’ll have to come a different way.” (Fitting to talk of directions…Lynde was formerly a cartographer.) We found him waiting near the dock he uses to ferry his oysters from Gay Island, where his parents built a house and boathouse years ago, and where he says he can harvest all year because the oysters are grown with ocean water continually flowing past, never freezing. Gay Island oysters are known for a pure ocean taste. We walked down to the boat to see some of his oysters in different ages and sizes, and to select some to take on the road. The shells of the oldest, at least three years and older, are naturally tinted green and purple. As the sun began setting over the cove, conversation turned to the years and patience needed for a life of oystering. And we started to shiver.

One more peninsula up the coast was the last destination of the day. When we pulled in to the Craignair Inn and Restaurant, we could see through the window a fire in the fireplace. We would sleep well tonight, but first we would dine on a few more oysters. The chef, Chris Seiler, was more than game to serve up some Pemaquids. (An admitted oyster fan, he says he saves the tag from every bushel of oysters he uses.) He went all out: oyster stew, oysters Bienville, oysters Rockefeller, and oysters on the half shell with a mignonette. It was a feast in small courses. Oysters Rockefeller is a house specialty, and reportedly one summer guest said Seiler’s Pernod-drenched version is so good that she wanted “to bathe in it.”

day two: spruce head to north haven

In the morning, we were back in the Craignair dining room bright and early for blueberry pancakes and bacon, and then we picked up the quest again with vigor, continuing on down the St. George peninsula. If I were an oyster, I would happily live in the rocky environs of Tenants Harbor and Port Clyde, but we found no oyster action there. (We remembered seeing a handmade OYSTERS sign in a yard on the peninsula a few years ago, but when we asked around, folks said they didn’t know of anyone harvesting anymore.) After stopping for a good cup of coffee at the Port Clyde General Store, we drove on to Rockland. Primo wasn’t open yet for the evening, and although the renowned restaurant typically closes from January through May, in peak season the upstairs bar has a following for its dollar oyster nights. Sometimes they even have Belons, the flatter, rounder European oysters that Julia Child wrote of eating in Provence and that were introduced to Maine waters in the 1950s. I’ve seen more than one local make a sour face and say they taste “just like a penny,” but the last time I had Belons I remember liking the striking metallic flavor. And the shells were so pretty I couldn’t throw them out.

I remembered something else too…having tasted North Haven oysters on a recent visit to the Oyster Bar, underground at Grand Central Station in New York. That memory led to our next move: buying tickets for the last ferry of the day to the island, due east in Penobscot Bay. With tickets in hand, we spent a couple hours doing a bit more oyster research. At RAYR, a wine shop and espresso bar in Rockport that is also a gallery for local fine furniture, I asked for a bottle that would go well with fresh oysters. Owner Jason Haynes walked straight to a 2009 Muscadet-Sevre et Maine. I liked his decisiveness—and his fishermen’s sweater. We bought the bottle and saved it for later. Our next stop was snug Rockport Harbor, with its wooden boat builders and iconic red boathouse over the water. Shepherd’s Pie is in a tall brick building above, and I had heard good things about the restaurant, which was opened last year by chef Brian Hill of Francine Bistro in Camden. At a few minutes past 4 p.m., we were the first customers inside and took up stools at the long bar, not far from the flames of the wood-fired oven. They serve roasted oysters at Shepherd’s Pie, something I hadn’t yet seen in Maine. (Oyster roasts are a winter tradition in South Carolina.) That’s our order, please. In a few minutes, out they came, roasted not in their shells but each in its own cup in an escargot plate, drenched in garlic butter and white wine. It was a bubbling hot mix of Paris and Pemaquids, and I loved every bite.

No second rounds, though. The ferry would be chugging off from Rockland Harbor soon. We drove back to the terminal, parked the car for the night, and filed aboard for the seventy-minute crossing. While sitting in the molded-plastic seats, we met Adam Williams, whose tan Carhartt jacket had a mermaid embroidered on the back—the logo of the North Haven Oyster Company. The owner and founder of the business, the guy’s also a good storyteller. As the boat engine hummed, he told us the roundabout way he got into oystering: growing up on the then-polluted Hudson River in New York, seeing an ad for Maine boatbuilding, making his way to Rockport, and then getting a job on schooners instead. Eventually, Williams ended up on North Haven for work and met the woman who would become his wife, Michelle, who is a North Haven native. She’d be picking him up at the landing that night. Would we like a ride up the hill to the Nebo Lodge? With the snow and darkness settling in, we took him up on the offer.

day three: north haven to belfast to the cabin

Decorated in the blues and whites of clouds and surf, the Lodge was a comfortable place to rest. We had the place nearly to ourselves, and we made our own dinner and breakfast in the microwave. (When the restaurant at Nebo is open, in-season and on weekends, there’s plenty of fresh gourmet cooking—and North Haven oysters are a specialty.) By morning, several inches of new snow had fallen. Williams had told us that he and his son Caleb would be going out oystering that morning, and we wanted to check that out before catching the return ferry. Wearing chest waders, the two walked into waist-deep water and filled bags of oysters while the sun climbed higher and glinted off the snow and ice. The white of the snow, the clear light, the frigid water, and the working father-and-son team made an iconic this-is-where-oysters-come-from scene.

Still riding the North Haven high, we hit Rockland with renewed energy for our final stops. At Jess’s Market, we fell in line among the Friday afternoon rush of haddock sales, and we ordered a half-dozen each of the three kinds of oysters in the refrigerator case—Weskeags, Little Islands, and Pemaquids. “Be careful with these Weskeags” the clerk said. “The shells are brittle so you’ve got to finesse them…but they taste good.” (We’d find out later she was right.) Then we trucked up the road to Camden and the Atlantica, where owner and chef Ken Paquin was looking out at the water. He said they had just seen a harp seal—a rarity for the harbor, which buzzes with yachts all summer. At a table overlooking the water, Paquin presented a plate of chilled Pemaquid oysters on a bed of seaweed, served up in a classic peppercorn-and-shallot mignonette with a few pomegranate seeds in each shell. It was lovely. And with a few sips from a split of Prosecco, those were a particularly delicious few minutes in the waning hours of our self-paced tour.

But we couldn’t linger. With the Bucksport cabin in our sights, we continued purposefully up the Penobscot Bay coast on Route 1, past Lincolnville Beach and Ducktrap Harbor. Down on the Belfast waterfront, we made a brief libation run to the Marshall Wharf Brewing Company. I was hoping they would have some of the molasses-black Pemaquid Oyster Stout, and they did, on tap for sample cups and growler filling. The Three Tides next door wasn’t open yet for the evening, but that’s where I first tasted icy Pemaquids a few years ago, and where I have ordered them on every return trip since, often followed or preceded by a plate of their Swedish meatballs—not sure why, but it works.

Now, here’s the capper. We’ve got a good-sized Franklin stove in the center of our place near Bucksport. When we got there with our sacks of oysters in hand, we lit a fire and finally opened that bottle of Muscadet. We sliced a lemon, spooned out some biting horseradish cocktail sauce, and shucked most of the Gay Islands, Weskeags, Pemaquids, and Little Islands for final tastes. Then, when the coals were glowing hot, we roasted the rest of the unopened ones for a second course, right there on the Maine logs. Contentment filled the room. In three days we had tried oysters from at least seven different farmers or harvesters, met more good people than I could count, and expanded our grasp of midcoast geography. It was time to close the Gazetteer and seek something else: sweet sleep.

– by Sandy Lang for Maine magazine, March 2011

THE HOG HIGHWAY

Chasing ‘cue across eastern North Carolina

The whole adventure was a lark, a two-day open-road bender. There was little planning. We unfolded a map during a visit with family down east in North Carolina and stitched a looping route from Wayne County southeast of Raleigh to Beaufort County in the east, to as far west as Chapel Hill—and back again. Our guide would be pork, specifically the vinegar-pepper whole-hog variety that gives the eastern part of the state its reputation for serving up some of the best ’cue in the country. We’d stay off major highways when possible, following two-lane asphalt lined with farmhouses and pine tree rows, tobacco barns and railroad crossings. My dream was to get to old-school places where the hogs had been cooked at least half the night over hot coals, and that they’d still have some left when we got there.

At Grady’s Barbecue east of Dudley (pop. 11,889), we missed our chance. This parlor looks just like I hoped it would, at a V crossroads, miles from town. By the time we rolled in after lunch hour, the pig cooked the night before was already chopped and gone. The “closed” sign was turned out. But there was Stephen Grady, the owner, still standing in the doorway of his white cinder-block cookhouse. We called out to him and he waved us inside, into the one-room building of brick pits and iron grills, of char and wood smoke. What we didn’t get to taste, we could smell. Stephen pointed at the underbelly of the cookhouse roof, where the rafters are smudged black from years of slow fires. “I burned the first roof off,” he said. That was more than twenty years ago, not long after he and his wife, Gerri, had opened the place. They’d planned to drive off that afternoon on a vacation. But hot fat and a roof built too low mixed to set the building ablaze. The couple never did take that trip. Instead, Stephen rebuilt with an almost steeple-like roofline that’s lasted for four nights of barbecuing every week, without burning, ever since. He grinned while looking at it. “I figured up that new roof pretty good.”

While we talked, Gerri went into the kitchen and pulled back the foil on some still-warm hush puppies, and she ladled up a couple of bowls of the most tender, flavorful black-eyed peas on earth. She poured big foam cups of sweet tea for us, and then we drove on. The Gradys needed to get home and rest. Stephen said he would be back that night around 10:30 to start the fires again; he had three more fresh hogs to cook, bought from a farmer about six miles down the road.

With that one stop, we’d already practically found my dream spot. But we drove on. This time we were heading to Ayden (pop. 4,622), where the wood-fired barbecue has been described as “veal-tender.” It’s the home of the Skylight Inn, known for the capitol dome that rises out of the roof of the plain brick building, staking its claim as “the bar-b-q capital of the world.” (When we were looking for the place, two local people didn’t know it as Skylight; instead, they called it “the Capitol” and “the place that looks like the White House.”) We got there during the afternoon “rush,” when suddenly six or eight people showed up, making a line almost to the door of the small half-circle dining room. Inside, there was little other sound than the rhythmic chop of cleavers on a wood cutting board; two young men worked over a foot-tall mound of barbecue under the light of a heat lamp, all in full view of the ordering counter. Like just about everyone else in line, we ordered and were handed plaid paper trays of chopped barbecue and milky green coleslaw, cups of pepper vinegar, and a plank of dense cornbread as big as your hand. Everyone was eating like it was their job, and the room was often unnervingly quiet. You could actually hear people’s maws at work—folks chewing, slurping tea. This was barbecue at its most serious.

A Barbecue Flurry

A few blocks away is downtown Ayden, which has a revitalization project going, lots of fresh paint and signs. My sister-in-law, who was raised about forty miles away in tiny Eureka (pop. 239)—where her family’s farm still grows soybeans and cucumbers—had suggested we check out Bum’s Restaurant on Third Street. There, Latham “Bum” Dennis served us a plate of pulled pork, mashed rutabagas, and greens, and then sat down to talk while we ate. Looking as fit as a man in his fifties, Bum (who later mentioned he’s seventy-two) has a large tattoo of a “Japanese lady standing sideways” in a green dress on his forearm, lots of stories, and a warm smile. When he and his wife, Shirley, bought the place from a cousin in the 1960s, they rolled kitchen equipment right down Ayden’s sidewalks. And these days, their son Larry does much of the barbecuing in the smokehouse out back. Bum says they cook over oak or ash, seasoning only with salt before the hog goes on the fire. At his farmhouse nearby, he plants a “little garden” of about eleven acres to provide most of the vegetables for the restaurant, including his delicious collard greens.

That’s the way this trip was, meeting people, talking about and eating barbecue, and settling in for long views of the countryside, sometimes feeling like we’d traveled back to simpler decades. Over and over, we were inspired to stop, or at least turn around for a better look at the scenery—Pickle Festival banners on NC 55 near Mount Olive and the massive pickle factory there; the tidy White Rock AME Church set back from Hwy. 301 in Micro; the red clay oval and bleachers at the Tri-County Kartway (intersection of NC 581 and NC 222 at Kenly); and the huge sow snorting through a pile of sweet potatoes and straw near a “pigs for sale” sign on NC 581 not far from Buckhorn Crossroads. We even made a side trip to see the jaw-dropping Nahunta Pork Center in Pikevile (pop. 719). It’s an entire grocery store of pork, with more chilled cases of ham and pork belly than I’d ever seen in my life.

By the time we got to B’s Barbecue in Greenville (pop. 60,476), the evening streetlights were already coming on, and its well-known “sold out of food” sign was tacked to the door. At the very large, busy Parker’s Barbecue in Wilson (pop. 47,804), where the servers are all men in white uniforms and paper hats, a manager told me they’d just served 120 Harley riders who’d called ahead, getting everyone seated in two dining rooms, and in and out within forty-five minutes. The manager, Kevin Lamm, also gave me directions to the Whirligig Farm I’d heard about in nearby Lucama (pop. 854). “Yeah, we used to go there at night…when your headlights hit the auto reflectors, it’s pretty cool.” I couldn’t wait to get there. So we followed Kevin’s directions, the most helpful of which was “You’ll think you’ve driven too far, but keep going.” After about eight country miles of anticipation, I got out of the car and stood there in astonishment. A man with a metal shop, Vollis Simpson, began creating these fantastical sculptures years ago, a growing collection that whir and clang into quite a racket up in the pine trees. It’s like watching an open-air kaleidoscope. I could have stayed much longer, just looking up and listening.

But we didn’t want to miss Allen & Son Bar-B-Que in Chapel Hill (pop. 54,492), so we kept going and made it in time for pulled pork with the most smoke flavor we’d taste on this trip, along with a warmed slice of cream cheese pound cake for dessert. Then for a taste we hadn’t planned, we made a fast stop for a modern take on the comforts of barbecue, at least in the look of the parlor. The Q Shack in Durham (pop. 217,847) smokes a wet and peppery pulled pork, along with pulled chicken, Texas-style brisket, and ribs. (One of the founders is Scott Howell, who has the very popular restaurant Nana’s a couple of doors down.)And here’s my lasting memory from the barbecue flurry: this from about a hundred miles earlier in Farmville (pop. 4,606), where there was an art deco marquee announcing a stage production of To Kill a Mockingbird. We stopped a few blocks farther down Main Street at the square cinder-block building that houses Jack Cobb & Son, and carried our trays of barbecue, slaw, and stewed cabbage outside to sit in its ramshackle (but tidy) screen house. That’s when it hit me, what a simple thing this all really is. If you chase barbecue dreams, someday, somewhere you’ll find yourself this way, too, sitting on a rusty folding chair in a town you’d never driven through before, eating vinegar-drenched lukewarm meat and sweet fried hush puppies from a foam tray. There’s no music. There’s no beer. But you take another bite with your plastic fork and think, damn, this is good.

– by Sandy Lang for Garden & Gun, published June-July 2009

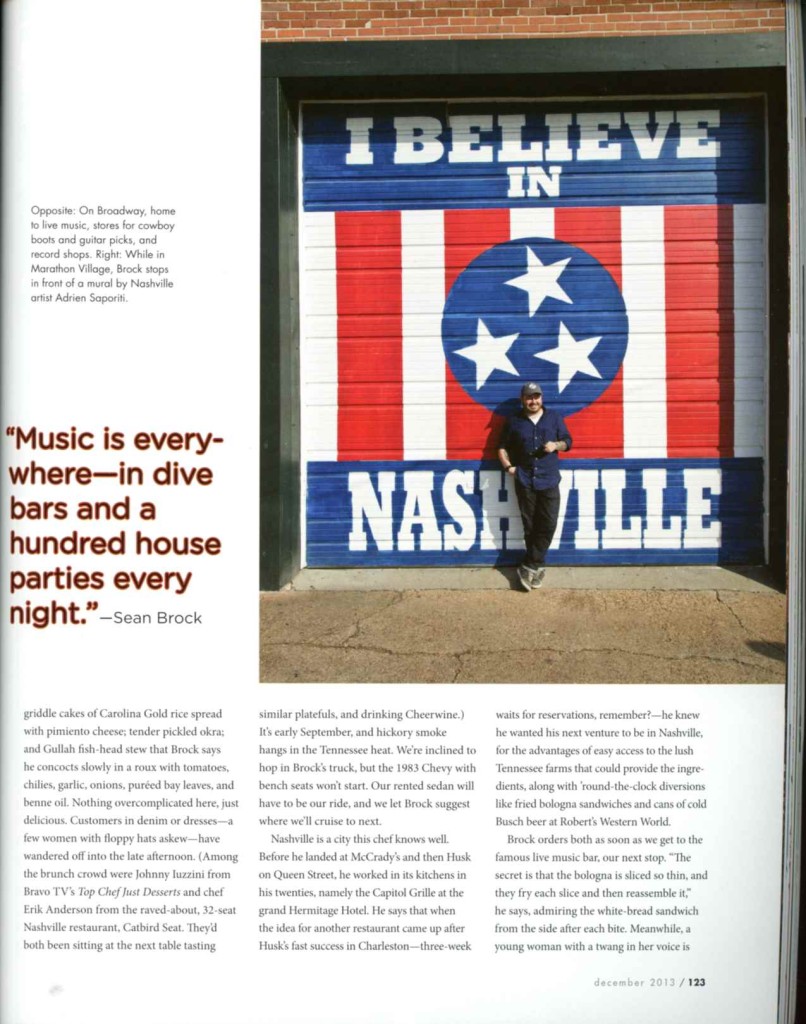

NASHVILLE ON FIRE

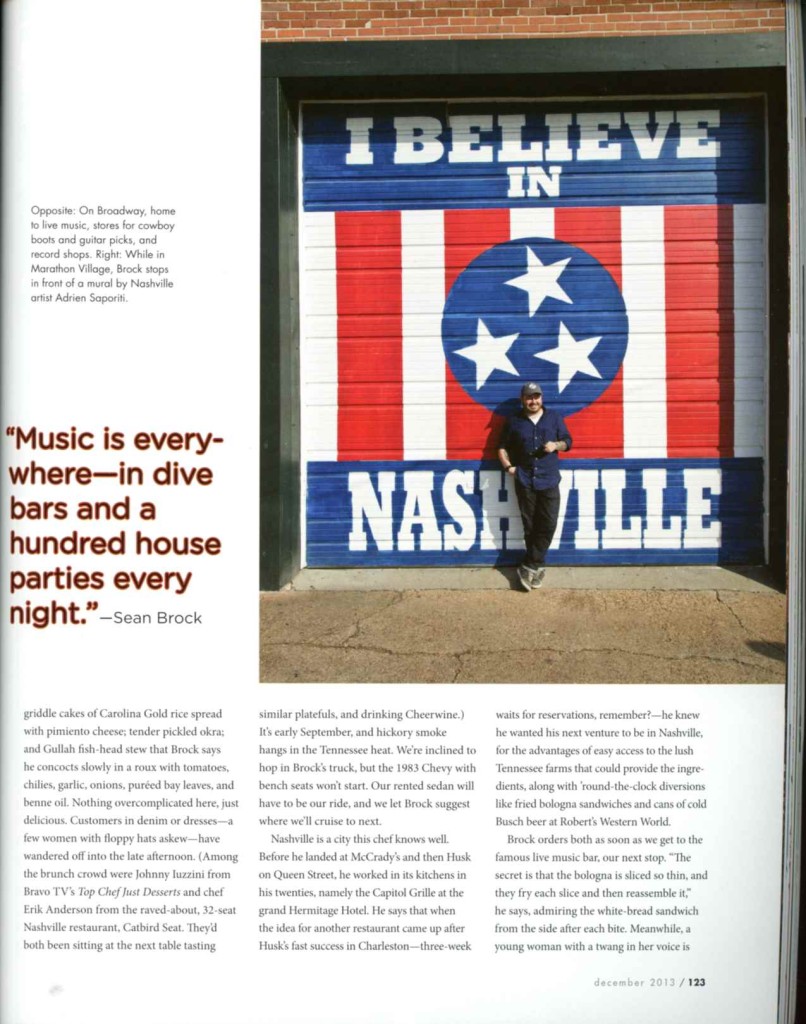

“Embers,” says Sean Brock. He wouldn’t want to have a kitchen without them. The deep-thinking chef with the devilish smile is leaning on his long-bed truck outside of a Nashville mansion—the historic house with triumphal arched porch openings is now home to the Tennessee cousin of Charleston’s Husk. Brock snuck off earlier this year to open the Nashville version, and the restaurant served up its first ember-fired meals as the Lowcountry was knee-deep in Spoleto.From this Husk, situated on a hilltop, the Music City rolls out below to the Cumberland River and the lights of the honky-tonks on Broadway. Every guest walking across the restaurant’s wood floors passes the iron racks of the busy kitchen’s open hearth. Flames lick the grates above, and pans of bone marrow, chicken, and sweet corn—some skillets perforated to allow direct contact with smoke and heat—are set right on the red-hot coals. A huge portrait of Willie Nelson in braided profile dominates one wall. It’s a fiery kitchen in the heart of the house. “Like the embers in Rodney Scott’s pit,” says Brock, referring to the all-night wood fires and shovel-loads of coals used for cooking whole-hog barbecue at Scott’s Variety in Hemingway, South Carolina.

That’s the heart-and-soul-driven Brock we’ve gotten to know in Charleston at McCrady’s and Husk and at farm dinners out on John’s and Wadmalaw islands. He’s always fast to give credit to the best cooks and makers of the world. Pretty gracious for a guy at the top of the ranks himself: James Beard accolades and TV limelight, including the latest episodes of The Mind of a Chef on PBS. But for a few days, Brock is game to put aside other projects that he’s got cooking for a romp around Nashville.

HUSKER-TWO

By the time we’re all in the Husk parking lot talking about embers, I’ve got a belly full of brunch, including the black-pepper biscuits with cream-rich, sausage gravy; hot griddle cakes of Carolina Gold rice spread with pimiento cheese; tender pickled okra; and Gullah fish-head stew that Brock says he concocts slowly in a roux with tomatoes, chilies, garlic, onions, puréed bay leaves, and benne oil. Nothing overcomplicated here, just delicious. Customers in denim or dresses—a few women with floppy hats askew—have wandered off into the late afternoon. (Among the brunch crowd were Johnny Iuzzini from Bravo TV’s Top Chef Just Desserts and chef Erik Anderson from the raved-about, 32-seat Nashville restaurant, Catbird Seat. They’d both been sitting at the next table tasting similar platefuls, and drinking Cheerwine.) It’s early September, and hickory smoke hangs in the Tennessee heat. We’re inclined to hop in Brock’s truck, but the 1983 Chevy with bench seats won’t start. Our rented sedan will have to be our ride, and we let Brock suggest where we’ll cruise to next.

Nashville is a city this chef knows well. Before he landed at McCrady’s and then Husk on Queen Street, he worked in its kitchens in his twenties, namely the Capitol Grille at the grand Hermitage Hotel. He says that when the idea for another restaurant came up after Husk’s fast success in Charleston—three-week waits for reservations, remember?—he knew he wanted his next venture to be in Nashville, for the advantages of easy access to the lush Tennessee farms that could provide the ingredients, along with ’round-the-clock diversions like fried bologna sandwiches and cans of cold Busch beer at Robert’s Western World.

Brock orders both as soon as we get to the famous live music bar, our next stop. “The secret is that the bologna is sliced so thin, and they fry each slice and then reassemble it,” he says, admiring the white-bread sandwich from the side after each bite. Meanwhile, a young woman with a twang in her voice is singing the Nashville classic, “Hey, bird dog, get away from my quail,” and the narrow dance floor in front of the stage starts filling.

The next band has a stand-up bass and a Stray Cats sound that makes you want to stay, but we can’t stop now. Brock suggests a late supper at Rolf and Daughters. Getting there for some “modern peasant food” is something I’d hoped to do in Nashville. Bon Appétit had just named it one of the top-five “Best New Restaurants of the Year,” declaring that chef Philip Krajeck was “put on earth to make pasta.” We feel lucky to get in. Brock is friends with the servers and Krajeck and immediately places an order for “the pastas.” Within minutes our table is laden with big bowls to share—of all five pasta dishes on the day’s menu—in shapes and ingredient combinations I’ve never seen. In the room of long wooden tables and softly lit bulbs hanging at varying heights, we’re stabbing our forks into twists of farro gemelli (spelt flour pasta) with kale and hen-of-the-woods mushrooms; rustic spaghetti with octopus and a chili kick; and the squat, ridged tubes of a black, squid-ink canestri pasta with shrimp and pancetta. The blond chef sits with us for a few minutes, pleased to see all the bowls being passed around. “This is the way I always hoped it would be,” he says.

MAKERS & MICHELADAS

Like life itself, this trip is not all about food. With a penchant for work shirts, Imogene + Willie jeans (the Nashville brand makes jeans for the Husk crew), and armfuls of tattoos—a newly inked cardinal, the state bird of Virginia (his home state), is still tender on his forearm—Brock’s wider interests spin toward culture, style, and design. We sample some of those Nashville highlights, too. The next morning’s first venture is to Marathon Village, a very cool reuse of the early-20th-century factory for Marathon Motor Cars. The four-block building has been renovated into studios for artists, a coffee shop, offices, galleries, a progressive radio station, and a distillery. In the natural light of tall, steel-framed windows, we find Otis James and his sewing crew using vintage Singer machines to make bow-ties, caps, handkerchiefs, and ascots in handsome tweeds, tiny floral patterns, and soft linen. Slim and sincere with pale blue eyes, James bicycled across America before coming to Nashville to sew and design. Here, he says, “there’s a sense of community among the creative businesses… and if you have a good idea, there aren’t a million people already doing it.” James adds that he’s just hired more assistants to sew for his growing line of tie-wear that now also includes flowing “lady ties.”

Down a few hallways is the workshop of belt- and bag-maker Emil Erwin—Emil’s last name is actually Congdon, and Erwin is the Tennessee town where he’s from. Congdon recognizes he’s part of an “explosion of craftsmanship” in Nashville. Many of the local artisans are in their twenties and thirties, and he works with his wife, Leslie, who happens to have their toddler son in tow this day. The room, rich with smells of canvas and leather, is filled with rolls and scraps of each, benches lined with tools, and buckles in chrome and brass. While I admire the stitching and sturdy designs, Brock orders a custom-made satchel as an anniversary present for his wife, Tonya. She’s a hands-on maker herself, by the way, and recently launched her own letterpress enterprise, Winding Wheel Press, in Charleston.

It’s energizing to glimpse Nashville’s artisanal side, and Brock suddenly has an idea for another stop, this time for chocolate craftsmanship. He makes a call, and within a few minutes we’re standing in a near fog of cocoa aromas at Olive & Sinclair Chocolate Co. Founder Scott Witherow, who worked several stints in Brock’s kitchen at the Capitol Grille, shows us the cocoa bean roaster, winnower, and the stacks of just-wrapped bars of Double Chocolate, Salt & Pepper, and Buttermilk White. Near the boxes of Bourbon Nib Brittle, he shows us a machine from the 1910s that features a rotating 2,500-pound stone wheel to press out the cocoa butter. The whole production is based on “antiquated and inefficient techniques,” he modestly explains, and it’s obvious this guy in round-rimmed glasses and a “Chocolate stone-ground in Nashville” T-shirt loves every minute of the work—and the results.

Everyone’s hungry now. We start with foam trays of fried chicken coated in hot pepper at Bolton’s Spicy Chicken & Fish, one of Nashville’s cinder-block meccas for heat. “Hot chicken is like a religion here,” Brock says as he sweats through two pieces and three iced teas. While it’s not the hottest any of us has ever had, it’s fried just right. He studies these Nashville specialties like a scholar. Back in the car, Brock tells us about the personal taqueria tour he’s been making, looking for the city’s best tacos and micheladas. That’s our cue to drive several miles out of downtown to try one of his favorites, El Tapatio on Nolensville Pike. It’s the kind of taqueria where the chicken, beef, tripe, and chorizo are cooked outside on the grill, and he’s excited to see that the barrel smoker out front is lit. “That smells like freedom,” Brock says when the smoke hits us. This is good. Tortillas arrive with grill marks, and the micheladas are served in stemmed glasses with fat globes rimmed with salt and chili flakes and bottles of Tecate still upside down in Clamato juice and limes.

LP PARLOR FINALE

With stomachs feeling the fire on the return drive downtown, we turn up the volume for another song by Jason Isbell, the Alabama-born singer-songwriter with Elvis-slicked hair who’s one of Brock’s favorites and obviously on high rotation with Nashville radio stations. Here in Music City, you can never forget that music is an elevated, living thing. “It’s everywhere,” Brock says, “in dive bars and a hundred house parties every night.”

The next day we go to more places where music, including fresh vinyl recordings, is revered. The Barista Parlor is essentially a coffee shop, but it feels more like a style collective. While LP records play, customers in the wide garage bays sip poured-over coffees and sit on stools fashioned from whiskey barrels. Employees in work aprons move with a gentle quietness that seems just right for easing into a drowsy morning. And while waiting for orders of biscuits and local jam, you can muse about the parlor’s nautical murals and vintage motorcycles with swooping lines.

A more raucous stop is Thirdman Records. The studio of musician Jack White has a small and curious store that’s a tribute to vinyl, selling record players, vinyl singles, and LP records. Visitors can strum guitars and thump cymbals here, and for $15, you can even cut a record in a booth. (Ask photographer Frank Edwards to hear his spontaneous, bluesy track.)

In the racks, I find a 45 made at the studio this year by Shovels & Rope. Along with the purchase of an Emil Erwin belt, that record becomes my favorite Nashville souvenir and lends another Charleston (by way of The Pour House) connection. “It’s impossible not to love Nashville right now,” Brock had said early on in the trip, and I can’t help but agree. It’s a great, maybe even a proud moment, to see Brock and the Charleston-born Husk add to the simmering, stylish Nashville scene—embers and all.

– by Sandy Lang for Charleston Magazine (photographs by Peter Frank Edwards)

THE NOMENCLATURE OF COLOR

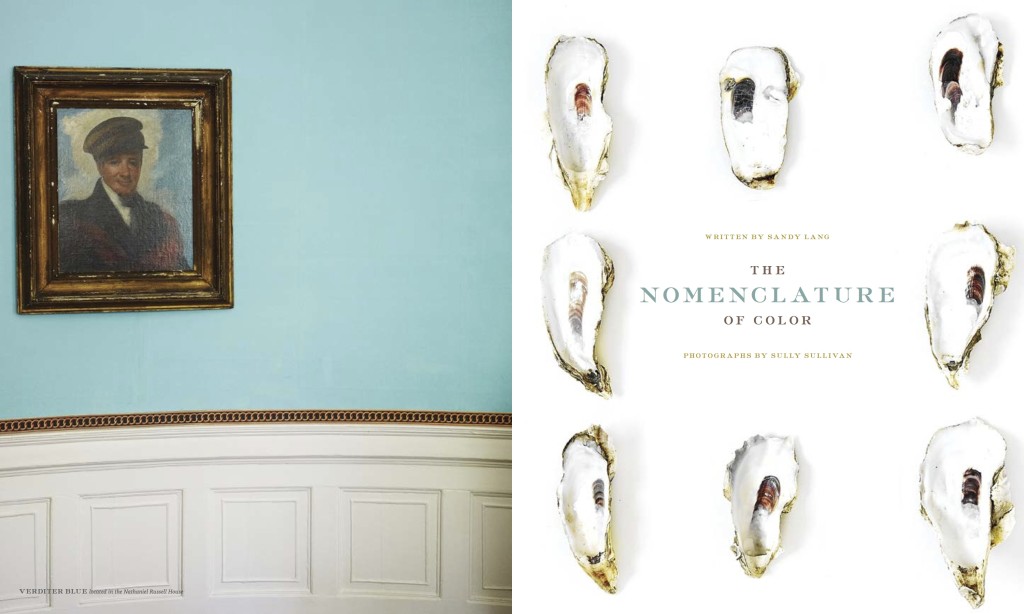

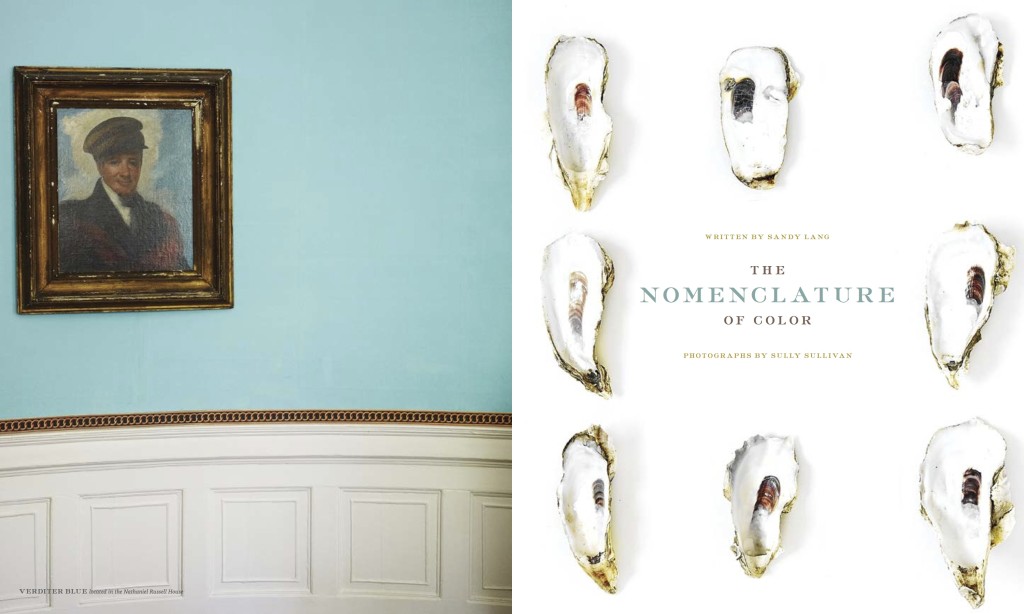

In a little-used, top-floor room of the circa-1808 Nathaniel Russell House on lower Meeting Street, the museum director opened the interior shutters of the tall windows on the west-facing wall. Light streamed in through the sparkle of dust hanging in the air. And there it was, high on the wall: Alicia’s Bedchamber.

Not just a pleasing hue of blue-green turquoise above the window—and a faded strip painted to look like crown molding—this patch of wall is something of a holy grail of Charleston’s historic paint colors. Valerie Perry, who manages the house museum, tells the story: when Hurricane Hugo landed in Charleston in 1989 and wreaked havoc with rain and torn rooftops, the swath of painted plaster was revealed. It was a blue-green revelation that led historians to become curious about what other shades may be hidden throughout the house, under the layers of 19th and 20th century paints and papers. Frank S. Welsh, an experienced paint analyst, was brought in and careful archaeological techniques were used – scraping with dental tools, etc. – to uncover colors not seen for a century or two. Then from 1996 to the mid-2000s, paint analyst and conservator Susan L. Buck completed a more extensive in-depth study of Charleston paint colors, particularly at the circa-1818 Aiken-Rhett House on Elizabeth Street, another museum house of the Historic Charleston Foundation.

This work inspired the development of a palette of Charleston paint colors, developed with the Historic Charleston Foundation, and including “Alicia’s Bedchamber,” named for one of Nathaniel Russell’s daughters. The once-hidden hue can now be seen and painted on Charleston walls again, along with other shades with similar lore that are part of the city-named collection. The colors are all around—so organic to our lives, we may not always notice. As we walk Charleston’s streets, lean on porch columns at cocktail parties, or slide our chairs up to dinner tables in friends’ homes, we’re often surrounded by shades with history and significance. On exteriors and interiors, there are walls the green of loquat trees, the gray-brown of wet cobblestones, the terra cotta of local bricks, the chalky-white of oyster shells.

For a primer on Charleston color, a good start is at the well-restored and furnished Nathaniel Russell House. “Everyone who visits, notes it for the free-flowing staircase, but I think of the paint,” says Perry, pointing out not just the walls, but also the creamy white paint on the iron balcony rails, and the burled wood grain painted on the tall front doors. The grand home’s 19th century residents and guests were apparently dazzled by color, with moods and hues changing from room to room. Many of the home’s original colors found during the paint analysis have been returned. On the walls that rise around the famed staircase is a buttercup shade of “Russell’s Gold.” There’s a peachy-pink in the curved-wall drawing room. (In the collection, that paint color is, in fact, named “Drawing Room.”) And there’s a deep wine background color in the cornice in the withdrawing room with the moniker “Withdrawing Room Red”. The most striking color in the house, though, is “Verditer Blue,” a bright azure painted on softly overlapping rectangles of wallpaper. Almost everywhere you turn, there is a richness of color. Bold shades on the walls are often echoed in the classic period paintings and portraits that adorn them.

By many accounts, the vibrant colors were a revelation when the paint was uncovered and documented. Today, the use of the historic colors is championed anew by Charlestonians like Richard Marks, an architectural conservator, and architect Glenn Keyes, who worked on the restoration of Kiawah’s 18th century Vanderhorst Mansion in the 1990s. Keyes said, “We knew that such colors were used in England in the 19th century, but for some reason, we thought they didn’t transfer here… it was a nice surprise.”

At his historic preservation-oriented firm, Keyes says he often consults the palette. “It adds a layer of authenticity to use these 19th century colors, particularly with houses of the same vintage.” One of the colors he uses often is the “Charleston White” for it’s “pleasing depth… it’s not so bright white.” Keyes also has a penchant for the buttery “Stucco Creamtone,” and for the darker taupe of “Samuel O’Hara Frieze,” another documented color from the Nathaniel Russell House. O’Hara was a Charleston painter who advertised in 1808 that examples of his work could be seen at Mr. Russell’s “new building in Meeting Street.”

Charleston Courier, May 14, 1808

Samuel O’Hara RESPECTFULLY informs his friends and the publick, that he has removed to No. 81, Meeting Street, corner of Hasell street; where he carries on the work of HOUSE and SIGN PAINTING BUSINESS, in all its branches… He begs leave to refer gentlemen to Mr. Russell’s new building in Meeting Street, for a specimen of his work, which he confidently believes has not been equaled by any in the city… ROOMS painted, in oil or water colours, warranted to stand as well over old paper as otherwise, Fancy chairs and bed and window cornices, painted and Gilted in the most fashionable manner, and on the most moderate terms.

“A wealthy landowner could express his wealth by colors,” says Furman Cole, Charlestonian and longtime co-owner of Brewer’s Paint Center downtown. There was an artisan quality to painting well into the 20th century, with painters mixing the pigments and tints into lime washes just before painting. Since Charleston single houses were generally oriented with windows facing either east or west, Cole says paint colors were often chosen for the daylight it would receive when it was used most. He still often sees dining rooms in darker and richer colors (where candles or lights would typically be lit), and drawing room walls in middle-range colors.

Color and paint traditions are also used in new houses. Keyes says that on Kiawah, he’s noticed residents using traditional lime washes on plaster and stucco. “The result is mottled, not solid,” he says, “and you get a rich patina you don’t get with paint… people are interested.”

So often in Charleston, inspiration comes from history. To see a lime wash downtown, there’s a striking example over at the Aiken-Rhett House. The brilliant orange-gold on the South facing walls is a recent addition, painted to match an original color found there. Inside the house, most of the finishes are raw and preserved, but unrestored. Even in the kitchen and carriage houses, there’s evidence of colored limewashes and faux finishes in yellows, blues, oranges and pinks. (The 20th century paint additions withstanding—the dark gray paint in the double drawing room was applied during the making of “Swamp Thing,” filmed at the house in the 1970s.)

Light plays on the Aiken-Rhett walls with colors muted by the time and wear of a century, or nearly two. Most rooms have few furnishings, and wallpaper is tattered in places, so it’s not hard to get close to the walls and see that there are earlier layers of intact, original paint. Under the high ceilings the day’s sounds, and quietness, lingers. Go there and your mind can wander, and wonder, of lives and colors past. And present.

– by Sandy Lang for Legends Magazine, 2012 (photography by Sully Sullivan)

GIMME SOME SUGAR, NORTH CAROLINA

Oh, what a sweet adventure. This sugary story could have started in any number of towns. With just a trifle of effort, it’s possible to discover independent, local bakeries in North Carolina offering hot doughnuts at dawn or slices of cheesecake at near midnight. You can find regional recipes and countless variations of baked delights across the state, from fresh apple pie along the Blue Ridge Parkway to cream puffs on the coast.

ASHEVILLE: The Sisters McMullen. This tour begins in mountain-edged Asheville, in earshot of a street musician with a guitar who’s singing about faded flowers and lost love. At the narrow Pack Square location of the Sisters McMullen bakeries, a.k.a. the Cupcake Corner, customers stand eyeing the glass case of pastries and trying to decide. Here, the Whoopee Pies are bigger than an overstuffed pulled pork sandwich at a Carolina smokehouse, and the day’s line-up of cupcakes includes versions with gooey lemon or raspberry fillings, and a single remaining, very dark chocolate cupcake baked with Guinness beer. (That moist, not-too-sweet cake didn’t last long.) Opened in 2006, the corner shop often has a line at the counter, especially on festival weekends when tourists and locals stop in for a black-and-white cookie or a croissant. A few minutes away at the sister location on Merrimon Avenue, owner Andrea McMullen Sailer points beyond the vintage, chrome stools with crimson upholstery that line a wall of windows. “I live just over that mountain,” she says, and talks of Asheville’s luck to be a city so thick with great neighborhood cafés.

HENDERSONVILLE: Mountain Pie Company. Merri and Bill Tyndall keep the dining room and bakery cases chockfull of baked goods and knickknacks in a 1950s-era former filling station that’s home to the Mountain Pie Company. Each table is decorated individually with different colors and patterns of linens, china and silver from their personal collection. A blue ribbon from the 2010 Western North Carolina Apple Festival adorns the pie case—earned for one Merri’s apple pies made with local Honeycrisps and a crust made with leaf-shaped cutouts. “The pace is good out here, and people can sit awhile,” Merri says of the store that’s a few miles outside of downtown Hendersonville on a hilly countryside stretch of Hwy. 25. Old-fashioned pie varieties like North Carolina Tart Cherry, Buttermilk, and Amish Shoo Fly Pie are specialties. The Tyndalls bake daily, but got to test their pie mettle recently when a bride-to-be ordered eleven different pie flavors for her wedding reception, held on the eleventh day of the month, on a North Carolina mountaintop.

CHARLOTTE: Savannah Red. Right where Charlotte is its most urban and buildings tower overhead, a 27-seat restaurant is quietly serving gourmet dinners with Carolina-sourced ingredients, and desserts that are decidedly southern. Savannah Red feels like a secret. It’s just a few steps from the lobby, but near-hidden in a red-walled, intimate dining room of the otherwise grandly-scaled Charlotte Marriott City Center on Trade Street, which also boasts a 1,200-seat ballroom. The starring sweet attraction in the modern space is the Krispy Kreme Bread Pudding, with a caramel-bourbon sauce that’s lit aflame tableside, as demonstrated by Chef de Cuisine Billy Brown, who hails from Ohio, but has stayed on in Charlotte after training in the kitchens of Johnson & Wales University. The dessert’s fiery effect mirrors the various forms of firelight captured in framed photographs on the wall above. “Couples like to share this one,” Brown says of the gooey confection. Not surprising in the sultry, Savannah-styled room.

MATTHEWS: Jimmie’s Sweets. This is a newer slice of Matthews, a modern take on Main Street called Matthews Station, and Jimmie’s Sweets draws a following of its own in the retail line-up. The story here is the pound cakes, including the Luscious Lemon and the Chocolate Silk, each baked in a bundt pan and drenched in a pool of icing. Baker Jimmie Williams originally opened his “Gourmet Sweets Bakery” in West Virginia, and later moved baking operations to the pastel-painted storefront in Matthews. He beams a 100-watt smile when he describes how he originally won over family and friends with the moist cakes years ago. Ever since, Williams has created countless “Jimmie” versions of made-from-scratch layer cakes, cookies, cinnamon buns, deep-dish quiches, and more than 150 varieties of his specialty pound cakes, often with “tunnels” of fruit filling that spills out from the middle when cut – crushed pineapple, homemade strawberry preserves, Chambord raspberry sauce, and more.

ALBEMARLE: Rosebriar. “The coconut pie is to die for,” a customer leans over to say, in that discreet way that let’s you know you’ve just been let in on something special. The scene is another busy lunchtime at the Rosebriar restaurant in Albemarle—open for just three midday hours, and only on weekdays. Set in a 1920s building that was once the mill grocery, waitresses shuttle back and forth to plate up slices of the day’s pie offerings from a case to the right of the cash register. Gail Burris, who owns the 25-year-old landmark lunch stop with her husband, Alan, arrives around 8 a.m. each day and typically bakes 15-20 pies before the 11:00 lunchtime opening, many of them topped with a tall layer of meringue. Pie flavors include Orange Creme, Banana Split and candybar take-offs based on Almond Joy and Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups. Her personal favorite is the Strawberry Coconut. “Now, don’t put me in front of a computer,” Burris says with a laugh. “But I can make me some pie.”

ABERDEEN: The Bakehouse. Near golf-loving Pinehurst, Aberdeen is home to an unlikely bakery/café that’s a big hit with customers in and out of the golf set. At The Bakehouse, Martin Brunner, an Austrian-born pastry chef in a tall white chef’s hat, creates éclairs, truffles, chocolate Sacher-Tortes with apricot preserves, and rounds of Black Forest Cake topped with curls of dark Swiss chocolate. The foundation of everything in the bakery, Brunner says, is the custard-filled Napoleon. “It’s the way to a woman’s heart.” Thanks to a glass window in the dining area, customers may order from a menu that includes fresh-made soups, salads and “Barcelona” burgers, while they watch the pastries and cakes being assembled by Brunner and his staff. The Bakehouse traces its beginnings to a family bakery opened in Austria in 1948 by Brunner’s grandfather. (Coincidentally, the Aberdeen store is now housed in a brick, North Poplar Street building that was built in 1948.) European influences at The Bakehouse also come from Brunner’s father who is the breadmaker, and from his Spanish wife and mother-in-law, who both work in the café.

GREENSBORO: Cheesecakes by Alex. Several parking spaces in downtown Greensboro are painted with one sweet word in all capital letters, “CHEESECAKES.” The parking deck is just off South Elm Street, and past an adjoining patio is the Cheesecakes by Alex store, with tables and a glowing fish tank on one side, and the kitchen and glass cases of cakes on the other. Here, customers filing in as early as 7:30 a.m. and as late as 11:00 at night jockey for views of the different cheesecakes—also macaroons, bagels, muffins, and sticky buns—while smells of coffee, caramel and cinnamon fill the space. Someone orders a “build-your-own cheescake… twelve slices of whatever you want,” and starts by selecting a slice each of Crème Brulee and Bananas Foster cheesecakes. Meanwhile, Alex Amoroso, who has lived in Greensboro most of his life, has the young staff laughing again. He’s the big personality and baker behind the treats, and is known for continually coming up with new recipes and promotions. “I’m looking for beta testers for this idea I have for a bake-at-home crumb cake,” he says to the latest batch of customers. “Any takers?”

BURLINGTON: Paul’s Pastry Shop. At 5:30 a.m. the doors are open, and the donuts are hot. “This is still the best country in the world. You can take an idea and make it work,” says Derek Spencer, who is up at 3:00 in the morning most days to make sure there will be donuts. He and his wife, Beth, own Paul’s Pastry Shop, situated in a former Hardee’s that’s just a two-minute walk from the original, much smaller location that had no seating, and was opened more than 60 years ago. In November of last year, the couple moved Paul’s into the roomy fast-food restaurant space with a drive-through window and booths and tables for dining. Cinnamon fritters, brownies, cheese rings and tea biscuits also fill the cases, but the trays of the 75-cent, still-warm, glazed donuts are the best-sellers, drawing customers from Greensboro, Durham, Chapel Hill and more. Spencer, who’s also a letter carrier in the afternoons, knows well the sweet, yeasty recipes, and the donuts’ appeal. “Lots of times, I’ll take a box of hot glazed donuts with me to the post office to share.”

RALEIGH: Hayes Barton Café & Dessertery. Two schoolboys duck in out of the rain and can’t believe their luck. It’s the Five Points neighborhood in Raleigh—home to boutiques, antique stores and a pharmacy open since the 1930s. The kids didn’t expect to see such huge slices of cake—Coconut, Boston Crème, a “Patty Cake” of white chocolate cake layers and chocolate mousse icing. (The boys end up sharing a slice.) Cakes are just part of the 1940s-immersed scenery in the Hayes Barton Café that’s decked out in chrome, checkerboard tile, and memorabilia from film, music and World War II. Frank and Marget Ballard created the lunch, dinner and dessert café 14 years ago in the former “greasy spoon” diner space that shares a doorway with the old Hayes-Barton Pharmacy. Ever since, customers have brought in celebrity and local war veteran photographs to add to the décor, which includes a 1940s photo of Frank’s parents Eula May and Bill Ballard as sweethearts, as well as images drawn by the senior Ballard when he was a cartoonist for the Raleigh Observer from 1951 to 1964.

BAILEY: Bailey Café. Near the railroad tracks and grain elevators of tiny Bailey (size: less than one square mile), the Bailey Café is situated between a storefront church and a florist. In a space that once housed a farmers’ mercantile, local resident Roddie Hancock has filled the old wooden store shelves with his personal teapot collection of more than 1,000 pieces. And from the kitchen, he and his staff prepare everything from collard greens and fried frog legs to an array of fresh cakes and pastries. “Everybody was making bets that we wouldn’t succeed, but here we are,” Hancock says. A sign for the café on nearby I-95 helps, and so does the shelves of cakes, from Carrot to Hershey Bar to Cherry Carmel Delight. “You can’t get some of these anywhere else,” Hancock says. He and his staff also make deep pans of banana pudding, and fry up “Jacks,” turnovers that customers can take on the go that are filled with locally-favorite flavors like apple, peach, and sweet potato. To be sure, Paris, France has never seen a crêpe dish like the “Hancock Special,” a rolled and fried crêpe with sweetened cream cheese, fruit topping, and whipped cream. “With that one, you don’t need ice cream,” he laughs.

GOLDSBORO: Bread of Heaven Bakery. In a town known for vinegar-based barbecue and country ham, a little bakery churns out the cake batter in a large plaza on Ash Street. Bread is not on the menu at Bread of Heaven, but cake is king—so many cakes it’s almost dizzying. In six, gleaming glass cases, owner/baker Sandra Williams displays whole cakes and slices of Red Velvet, a Black & White Cake with a frosting thick with crumbled Oreos, a 7-Up Cake that involves lemon pudding, and a Pig Picking Cake that’s layered and topped with toasted pecans, shredded coconut and pineapple chunks. Bar cookies, Ritz crackers dipped in white chocolate, and pies are in the mix, too. Williams’ husband, who she says always shreds the carrots for the Carrot Cake, is a pastor, and contemporary gospel music can be heard from the kitchen, where baked goods are frequently cooling. When customers walk in, Williams sets aside the baking and attends the counter. The youthful grandmother in a white chef’s coat greets anyone who’s dazzled by the choices—and that’s most people—with a soothing, “Hey baby,” and asks what she can box up for them today.

MOREHEAD CITY: Seaside Cheesecake Dessert Shoppe. Bogue Sound is within a couple blocks of this Crystal Coast stop with lavender shutters. The interior looks part bakery, part living room, and part wine shop, with a small rack of select wines—bubbly Italian Prosecco to Côtes du Rhône reds. Co-owners David Scoggins and Forrest Berry, Jr. are both from Burlington, and bought Seaside Cheesecake Dessert Shoppe in 2010 from the original owner. They’ve definitely made the small store their own, adding to the menu, expanding hours to stay open year-round, and redecorating the space to include plush, upholstered seating. The men say the shop is best-known for its Piña Colada and Turtle cheesecakes (in white and chocolate versions), and they also make more than 50 other cheesecake flavors, along with mini cream puffs, key lime pies, and batches of chocolate chip cookies that typically sell-out daily. “We call it the ‘little bakery with big taste,’ “ according to Scoggins, who says the locals have been terrific customers. “Morehead City is a very cool place. Life is easy.” Then, as if on cue, he excuses himself to help prep a cheesecake order—for an afternoon party on a yacht.

WILMINGTON: Sugar on Front Street. The neon sign in the window glows with the words OLD BOOKS. Step into the 30-year-old bookstore, past the first sections of hardbacks and paperbacks, and just across from wall-spanning bookshelves that include the likes of a 1946 biography on Balzac, and you’ll find Sugar on Front Street. Opened in 2010, the tucked-away bakery is where readers gather at a few small tables and six mismatched stools along a counter to sip locally-roasted coffee and taste whatever Samantha Smith is baking—scones, Heirloom Apple Crumb Cake, Sour Cherry Pie, Lemon Zinger Cake. The ever-changing offerings of old-fashioned baked goods are “very rustic and not glamorous looking,” Smith admits. She’s modest. Her background as a professional pastry chef led her to open this place of her own. Everything is mismatched and vintage at Sugar, on purpose. “I have a problem. I like clutter,” the young baker says, adding, “Did you see my old Toledo Scale?” The hulking antique near a display case looks heavy, and Smith’s warmth and enthusiasm for baking is infectious. While she works in her ponytail and apron, customers gather to watch, and sometimes even bring recipes and old cookbooks to share.

Books, coffee, cakes and conversation—this last stop on the North Carolina dessert tour, like so many of the others, sure feels like home.

– by Sandy Lang for Our State, published February 2012

LIFE BY TIDES

Paying attention to the rise and fall, and to what the water brings.

On a sailboat we called the Eel Pye, we’d drifted right up to a dozen or more dolphins that were in a swirl, almost a frenzy, of fishing. It was a summer afternoon on the Fort Johnson side of the harbor, where the water was mixing with a changing tide. It was one of those scenes that gets seared in memory, a little movie to be played later—the dolphins’ slippery gray backs rising over and over, twisting in water that popped with a school of silvery fish.

Tides come and go, and things happen. On that old 22-foot Eel Pye, we’d let the rush of the changing tide pull us. The boat was moored in Wappoo Creek, a channel that connects the Ashley River end of the harbor with the Stono River. The currents there are famously strong, and we decided to make the most of it. I’d strap on flippers and jump in, swimming against the flow, and then turn around and let the water pull me back to the boat. It was such easy floating. And whenever I dunked under, I would hear so much life. Unlike freshwater lakes, where all you hear is your own splashes, the riverbed offered up a constant clicking (of crabs? oysters?) and bubbles rising. The creek water on my lips tasted salty and thick, like a tea of pluff mud and decaying marsh grass.

I loved to swim from that boat, until she was sold, but there are other stories of tides and boats and dolphins. One summer evening, on a swim around the pools and sandbars that build and fade with the tides on Sullivan’s Island, two dolphins surfaced so near and so many times I thought I’d get to touch one. I watched and called to them as the sun lowered, and they eventually swam off.

Back over near James Island, the currents and tides once brought in a beautiful wooden yacht that stretched at least 30 feet, with CONTESSA lettered in gold paint across her transom. We were out on a fall afternoon ride in the johnboat when we first saw her, stranded and abandoned in a creek off the Stono. For the next few weeks, we kept checking on the once-elegant boat, passing near.

Before long, the Contessa started a slow tilt in the low tides, and the lean got more exaggerated each day. We’d motor up sometimes and touch the wooden hull, and, when the tide was good for getting there, we ferried a few friends out for their own close-up look. Everyone made up stories about the impressive boat’s past—where she had come from, who owned her and left her, and why. But we never knew the real story, only what we could imagine. Then one day, the Contessa was gone. In my mind, I pictured the tides and mud had finally swallowed her.

Yesterday afternoon on a run over the Stono River Bridge, I looked down at the same swelling water and wondered what’s next. Around here, that six feet or so of ocean is always coming and going—mixing things up and adding a little mystery. Just the way I like it.

– by Sandy Lang for Charleston Magazine, January 2010 “The Odes Issue”

CRESCENT CITY CHRISTMAS

In New Orleans, traditions are as thick as roux. To get your fill in December, just follow the firelight.

When Louis Armstrong put his rolling, gravelly vocals to smooth brass on the swinging 1955 recording of “Christmas in New Orleans,” the distinctive holiday appeal of his hometown was set. Armstrong’s voice is like New Orleans itself—a blend of rough edges and refinement, unlike anything else. And in December, the well-worn and mightily loved Crescent City is decked out in lights, bows, and sparkle, ready for the season’s pageantry. Fetes start early, with a month of Réveillon dinners—often all-evening affairs where the Cajun-spiced and Creole-sauced courses keep coming. Celebrations culminate with towering bonfires ablaze on the levees, lighting up the bayou on brisk, year-end nights.

Here are some of the traditions any New Orleanian worth his Sazerac wouldn’t miss. Cue the music…’Cause it’s Christmastime in New Orleans.

Group Sing

Around sunset on the Sunday before Christmas, locals and visitors break into carols as they make their way through the French Quarter for the free Caroling at Jackson Square. In front of the tall spires of St. Louis Cathedral, volunteers hand out candles and song sheets, flames are passed from person to person until the whole square is aglow, and the voices sing into the evening with “Joy to the World,” “Silent Night,” and all manner of fa la la.

Gumbo Nights

Seasonal custom—and common sense—calls for fasting before a Réveillon night. The dinners are borne of the Creole tradition of serving a meal that could last until dawn after midnight Mass on Christmas Eve. (Réveillon is French for “awakening.”) Dozens of New Orleans restaurants, including such classics as Antoine’s and Arnaud’s, now serve prix fixe Réveillon menus of three, four, five, or more courses throughout December—from bisques to baba au rhum. Patrons dress in dinner jackets and cocktail dresses and linger at tables for hours. A dining room decked out in gold-painted magnolia wreaths marks the Réveillon season at Arnaud’s (504/523-5433), the 93-year-old landmark on Rue Bienville where guests sip icy gin cocktails, watch a jazz trio sway, and dine on such specialties as Gulf Fish Courtbouillon, an intoxicating, Creole-spiced fish stew. Several streetcar stops away, JoAnn Clevenger, owner of the cozy Upperline (504-891-9822), strolls from table to table in a red dress, pausing here and there to bring more rémoulade or share selections of her favorite places in New Orleans, from independent bookstores to art galleries.

Sparkle In the Lobby

Just about everyone in town takes at least one lingering walk along the marble floors of the swank, block-long lobby of The Roosevelt Hotel (504/648-1200). This hotel, refurbished since Hurricane Katrina with a $145 million renovation, hosts a fantastic annual display of trees and twinkling white lights. On a smaller scale but worth a stop when on Royal Street is the classic Hotel Monteleone (504/523-3341). The hotel hosts caroling choirs from New Orleans schools near a tall tree in the lobby. The Columns Hotel(504/899-9308), an 1883 Italianate mansion on St. Charles Avenue, dresses up for the weekly Champagne jazz brunch on Sundays with bough-decked porches and garland swags throughout the mahogany-paneled parlors.

Festive Sippers

In the shorter daylight hours of winter, Big Easy mornings of coffee with chicory turn to afternoons and evenings with cocktail options aplenty. At The Bombay Club (800/699-7711) in the Prince Conti Hotel, the rich Eggnog Noël blends nog with a jigger of butterscotch Schnapps. Tucked in Arnaud’s, the French 75 Bar (504/523-5433) serves up a Christmas spirit, The Contessa, a gin-based libation of grapefruit juice, Cranberry Cordial, Aperol, and Angostura bitters. And half-bottles of French red wines start at $11 in the cafe at the 214-year-old Napoleon House (504/524-9752), where the well-worn patina and portraits of Napoleon bolster the corner house’s charm. On December afternoons, the bartender shakes up frothy Brandy Milk Punches, one after another, topping each with a sprinkle of nutmeg.

St. Charles Tours

One of the hottest tickets of the season gets you inside some of the most splendidly decorated Garden District homes during the 36th Annual Holiday Home Tour (December 10-11; $35), organized by the Preservation Resource Center of New Orleans. The seven homes with open doors for this year’s lineup include a circa-1875 Italianate residence on Prytania Street with double galleries (two stories of columned porches) and a grand home on St. Charles Avenue where the annual Mardi Gras king always stops for a formal toast. Local musicians play at every house, and tour-goers are invited to stop for gumbo and po’boys at the tour’s holiday cafe in Trinity Episcopal Church, nearby on Jackson Avenue.

Creole Food Traditions

This time of year, New Orleanians have a peculiar attachment to the mirliton—known as the christophine or chayote in other parts of the world. Lumpy and pear-like, this mild-tasting gourd is conspicuously stacked in markets around the city in fall and winter, bought by residents who bake the holiday staple into pies or roast and scoop out the insides to mix with shrimp, sausage, or crabmeat. Palm-size mirliton pies are sometimes offered at Creole favorites such as Domilise’s Po-Boys and Bar (504/899-9126), and whole mirlitons can be bought, in season, at the Crescent City Farmers Market (504/861-4488).

Local Trinkets & Treasures

If you’re still shopping for the season, Le Jouet (504/837-0533) in Metairie will give you a nostalgic nod to the toy stores of old. Hands-on, no-battery-needed gadgets and games—disappearing ink, jigsaw puzzles—along with dollhouses and wooden train sets stock the aisles. An open doorway gives a view of staff assembling toys and wrapping gifts in a busy scene that looks like the workshop of Santa himself. Uptown on Magazine Street, the Longshore Studio Gallery (504/458-5500) displays art and furniture—vintage chairs reupholstered in slick, brightly colored vinyl; paintings that often feature fashion icons in colors so bold you’ll think you stepped into a Mardi Gras parade. Also on Magazine, Sucré (504/520-8311) makes a sweet stop for delicate macaroons, chocolates, and decadent pastries. Several blocks away at Mignon Faget (504/891-2005), find NOLA-inspired jewelry, including a series of pendants honoring the closest thing to snow in the bayou—the shaved ice “snowballs” scooped up at stands around the city.

Lighting of the Levee

Fire and water find their mix around New Orleans at Christmastime. According to Cajun tradition, bonfires illuminate the levees of the Mississippi River to help guide the way for Papa Noël. Algiers Point on New Orleans’ West Bank, a short ferry ride from the foot of Canal Street, held its first organized bonfire since Hurricane Katrina last year and is planning another for the first Saturday in December. In St. James Parish, about an hour west of New Orleans, the small town of Lutcher hosts the 22nd Annual Festival of the Bonfires, featuring a gumbo cook-off, a gingerbread-house contest, and a nightly bonfire after sunset. There, visitors may even buy miniature replicas of the stacked-wood pyres and take them home to await Papa’s return. And on Christmas Eve, friends and families gather to light bonfires along the levee in a tradition that has grown so much that Gray Line now offers a Bonfire Express motor coach tour.

– by Sandy Lang, published in Southern Living, December 2011

SECRET SUPPERS

A growing number of daring chefs and adventurous foodies have reignited the old Southern tradition of secret supper clubs. Eating out may never be the same.

The plates of creamed kale and fried rabbit were going fast, passed from person to person down one long table set in a Texas pecan grove. It was a sultry evening on a four-acre urban farm in east Austin, where forty-three people sat in mismatched chairs for a family-style dinner of eight courses in the lamplight. An old door turned over on sawhorses was the prep table, and Jesse Griffiths, our host and chef, cooked mostly at a table-height iron grill with a bottom tray that—by consensus of several supper guests—was once a feed trough. The fryer, a large cooking pot over a portable propane flame, was behind him. And the whole setup was under the porch roof of a farm shed.

He’d been cooking like that for hours, handing plates as soon as they were ready to his small crew, including his wife, Tamara Mayfield, who wore an embroidered summer dress, her brown hair in pigtails. A few yards from the long table, he cooked up pan-fried red peppers as big and sweet as strawberries, homemade jalapeño sausages, and smoky Gulf shrimp wrapped in grilled allspice leaves—all Texas ingredients.

This was a food-loving crowd, and they were eating it up. During the cocktail hour and between courses, people would often amble over to check out the cooking. As he turned quail over hot oak coals, Griffiths told stories: He told about the time he worked two weeks at a restaurant in Mexico that served only spit-roasted goat, turned in a coal-fired pit in the floor. Another time he caught the six pigeons he needed for a squab dinner by using some string, a box tilted up with a stick, and some chicken feed. Then there was Loncito, a lamb rancher, who talked of hosting long weekends at a South Texas hunting camp with two kitchens, where everyone takes turns cooking. A woman from the corporate offices of Whole Foods was there, of course. (Austin is the chain’s headquarters.)

The dinner that night was one put on by a two-year-old supper club in Austin, part of the now-simmering supper club scene in the South. As with many of the other secret-public grassroots clubs, Jesse and Tamara had started theirs with a small idea—to have one dinner on one night, inviting people to slow down for a few hours of good food and wine. More than two years later, the couple is still often cooking for a crowd on Saturday nights. And this is not just happening in Austin. In the Carolinas and Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Texas, and more, food-minded strangers are gathering at long tables to meet others and eat well. Operating outside the realm of official restaurants, this new wave of Southern supper clubs has sprung up in just the past two to three years. Upstarts in the Northwest, Midwest, California, and New York take earliest claim for such dinners, sometimes describing the meals in terms of a social movement, or even a revolution.

The South, though, has a tradition of secret supper clubs, of gathering around food for food’s sake. At clandestine gatherings of the Hot and Hot Fish Club in the early 1800s, some thirty to forty landowners (and at least one South Carolina governor) would meet on fishing ground hummocks around Pawleys Island and Murrells Inlet. The story goes that the men would fish all morning and then cook the catch for a dinner of at least two courses, the second always better than the first—making it hot and hot. The club was “dedicated to epicurean pursuits,” and besides fish, everyone was required to bring champagne and brandy to share. I often heard of this fish and drink lore while growing up near Murrells Inlet, and I thought of it again while going to a granddaddy of today’s supper clubs, this one held at John Henry Whitmire’s house on the Waccamaw River, a few miles inland of Pawleys Island. Organized by Outstanding in the Field and chef Jim Denevan—who since 1999 has hosted dinners all over the country, with fans following along as if it’s a band tour—the event was sold-out four months before the exact location was announced. And once there, more than 150 guests passed platters of local-caught wahoo along a looping line of tables at the edge of the old tidal rice impoundments.